Resisting the Japanese: The Rival Chinese Resistance Movements in WWII

January 27, 2014 in general history, History, History of China, History of Japan, Pacific History

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1941) merged into the Second World War following the attack on Pearl Harbor. After that, historians refer to the continued war in China against Japan as part of the Pacific Front of WWII. But these types of labels serve to obfuscate the shifting loyalties and general lack of ideological coherence of the global war in question, and of each front of that war, as participants switched sides and coalitions shifted. In its resistance against the Japanese, China received aid from Germany, the Soviet-Union and the United States — although not all at the same time.

During a time of war and grave national calamity, we may expect rival factions for internal control of a country to band together to fight the common enemy. Idealized depictions of allegiance also foster a view of allies who choose one side of an international dispute and stick to that side until the war is over. Generalized historical accounts of the era do tend to describe events in broad brushstrokes, speaking of th e Allies versus the Axis, or of the Americans as a homogeneous monolith, rather than the FDR administration as opposed to its detractors, but in reality the subtle distinctions and gradations within a nominally united group are very telling. Infighting continues while a war is in progress, and the true winners are those who end up on top, (e.g. Soviet Union) regardless of which side ( Axis or Allies) emerges as victorious.

e Allies versus the Axis, or of the Americans as a homogeneous monolith, rather than the FDR administration as opposed to its detractors, but in reality the subtle distinctions and gradations within a nominally united group are very telling. Infighting continues while a war is in progress, and the true winners are those who end up on top, (e.g. Soviet Union) regardless of which side ( Axis or Allies) emerges as victorious.

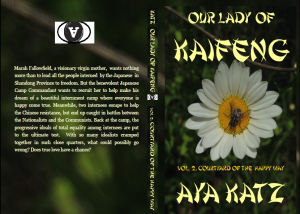

In China, during the Japanese occupation, there was a very active local resistance movement in Shandong Province. In fact, there were two such movements: the Nationalists and the Communists. When they were not engaging the Japanese, they were intent on destroying each other.

The lack of cohesion among the Chinese resisting the Japanese can be in some measure attributed to the lack of cohesion on the the part of the ever changing membership roster of the Allies and the Axis in Europe and the Pacific as the war progressed.

“Britain, the United States and Japan were drawn towards a Pacific war after Japan signed a Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy in late September 1940, and sponsored a collaborationist government in Nanjing, formed in March 1940 and led by Wang Jingwei. The United States and Britain responded by granting China loans and imposing economic sanctions against Japan.” (Lai 2008.134)

The Soviet Union was a wild card with no particular allegiance to any cause but its own. Though the Soviets allied themselves with Germany during the beginning of the war in Europe and the 1939 invasion of Poland, by 1941, due to Germany’s aggression toward Soviet-held territories, the Soviet Union joined the Allies.

According to Sherman X. Lai, the Soviet Union supported the Chinese Communists and supplied them with weapons, but there was also some negotiation by Stalin with the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek. Anything was possible, and the parties to these negotiations were motivated primarily by practical considerations, rather than any allegiance to ideology or to a nominal side in the international struggle for power. (Lai 2013)

Early in the Sino-Japanese war, Joseph Stalin was worried that Mao Zedong’s focus was too much on territorial expansion against the Nationalists, rather than fighting the Japanese. For this reason, despite the Soviet Union’s theoretical support for the the ideology of the Chinese Communists, Stalin also helped to arm the Chinese Nationalists. (Lai 2013.5)

Early in the Sino-Japanese war, Joseph Stalin was worried that Mao Zedong’s focus was too much on territorial expansion against the Nationalists, rather than fighting the Japanese. For this reason, despite the Soviet Union’s theoretical support for the the ideology of the Chinese Communists, Stalin also helped to arm the Chinese Nationalists. (Lai 2013.5)

The eventual outcome of the war between the Nationalists and the Communists was to be decided not only by military means through skirmishes and pitched battles, but even more so by behind the scenes dealing in currency and munitions.

According to Laurance Tipton (1949), a British escaped internee who served with the Nationalist resistance, General Wang Yumin (王豫民) who was at that time in charge of the Nationalist resistance in Shandong Province, issued his own currency and prohibited the use of any other currency in the area that he controlled.

Tipton (1949.120 ) writes:

“Under Japanese occupation, the Chinese National currency in North China was declared illegal tender and was replaced by the Japanese issued Federal Reserve Bank notes. But although Chinese National currency was forced out of circulation in the larger cities and railway towns, it was still current in the interior. As Chief of the Financial Department, Yu-Min’s first step was to print and circulate resistance money, which he exchanged for Chinese National Currency, silver dollars and gold bars at specified rates of exchange. At the same time he issued a proclamation prohibiting the use of any currency but the newly issued ‘resistance money.’ As the funds in the exchequer grew, so an increasing number of purchasing agents were dispatched to obtain ammunition, but, still dissatisfied with the results, Yu-Min continued to press for the opening of their own munitions and arms factories and finally won his point.”

According to Sherman Lai (2008) the Communist resistance eventually proved more successful not by implementing the principles of communism — redistribution and collectivism — but by reviving the feudal system of landlords and tenants that had operated in China for thousands of years prior to modernization.

Rather than attempting to reform society or to level any social stratification of which communism did not approve, the commissars recruited high level people in the existing order of things along the country-side in order to help them gain control.

In defense against banditry, local society was protected by powerful families who built fortifications and maintained private security forces. Those powerful families, also de facto bandits, stood in the way of the 115th Division’s … deployment southwards. In the campaign to gain a footing in this strategic region, Luo Ronghuan, its commissar, showed diplomatic skills. He approached a few prominent semi-bandit families who had displayed patriotism, seeking to persuade them to join the CCP-led anti-Japanese United Front. (Lai 2008.126)

Equally interesting is the fact that trade, not warfare, played an important role in strengthening the Chinese Communist Party in Shandong. It is easy to forget that the entire purpose of war for a free nation is to keep trade routes open. But a corollary may be this: that even during outright war, trade in staple goods and exchange of currency must continue to exist. Whoever corners the market on trade eventually wins the war. For the Communist Party (CCP) of Shandong, defeating the Japanese was partially made possible by trading with the Japanese.

Sherman Lai sums up the situation:

” ..the CCP in Shandong not only controlled economic affairs within its territory, but also obtained access to territories under enemy occupation through manipulation of currency exchange rates and by controlling the trade in staple grains, cotton, salt and peanut oil. As a result, trade with occupied China and with the Japanese invaders became the principal source of revenue of the CCP in Shandong as early as the second half of 1943.” (Lai 2008.i)

The greatest success of the Communist Shangdong Bureau during the Japanese invasion was their “red banking system.” Recognizing that simply printing money would result in devaluation, the Communists sought to corner the real market in agricultural staples for the purpose of trading for other goods. They realized that private enterprise in agriculture was the real tax base under communist control, so they encouraged local farmers.”The regulation of trade was intended to barter surplus products made in the CCP zones for needed supplies from the occupied zones” (Lai 2008.301) They founded their own bank and saw to it that the currency it printed would be more attractive and more stable than those issued by the Japanese collaborators or the Nationalist opposition.

The core of this system was the North Sea Bank (Beihai Yinhang) …. one of the three forerunners of the People’s Bank of China, China’s current central bank. Its banknotes, the beipiao (北票), spread from Shandong throughout eastern China and remained in circulation until December 1949. (Lai 2008.217)

Toward the end of the war, at a time when the Nationalist forces were crumbling under economic pressure and the Japanese themselves were weakening due to lack of supplies, the Chinese Communist party was taking in income through trade. They were a successful business concern, operating in a highly chaotic market.

It was not until the summer of 1944, after the invasion of Normandy and after the Japanese suffered a grave reversal in the Battle of the Philippine Sea that Mao started to prepare to implement the collectivization of agriculture that was to be the hallmark of his peacetime reign.

The nominal communists defeated their nationalist rivals and their imperialist invaders by being more successful capitalists. Once they had done this, they could afford to show their true colors. This is just one of the many ironies of a war with ever-shifting allegiances, multiple causes and fronts, which today, for some reason, is viewed by many in the Western world as the only truly “moral” war.

REFERENCES

Lai, Sherman Xiaogang . 2008. Springboard to Victory. http://qspace.library.queensu.ca/bitstream/1974/6186/1/Lai_Sherman_X_200809_PhD.pdf

Lai, Sherman Xiaogang. 2013,. A war within a war: the road to the new fourth army incident in January 1941. http://booksandjournals.brillonline.com/content/journals/10.1163/22127453-12341249;jsessionid=m1l3vwtlvkh1.x-brill-live-02. Journal of Chinese Military History,

Lunghu, 2012. Blog Post: Part Deux: East of the Mountains. https://lunghu.wordpress.com/2012/11/

Tipton, Laurance. 1949. Chinese Escapade. Macmillan and Company, Ltd.

Recent Comments