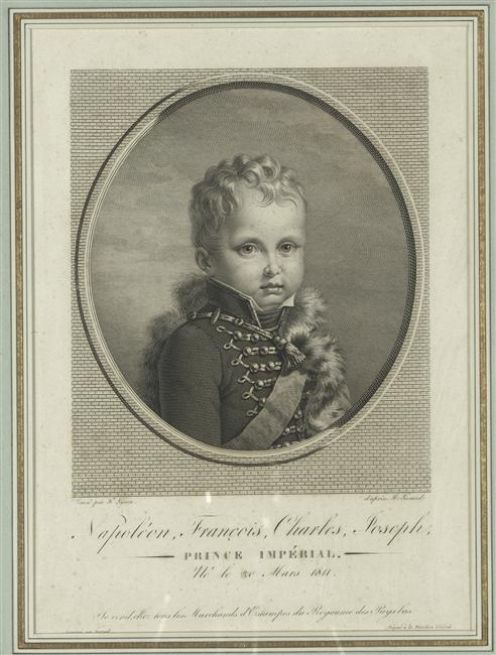

Napoléon François Joseph Charles Bonaparte – Great Expectations

With the birth of most children, there are all kinds of exciting possibilities and great expectations of what kind of person this new life will grow up to be. Sometimes a child comes into this world only with expectations upon the part of his parents and immediate family. While for others the expectations of the world might prove to be like the weight of the world in the hands of a babe. Such, was the birth of Napoléon François Joseph Charles Bonaparte, the only son of Napoleon Bonaparte.

He was expected to be the next ruler of France and for Napoléon II, no higher expectations were perhaps heaped upon one child than this little boy. Therein lies the problem — the trouble with great expectations are that they are merely expectations, and life has a way of turning expectations into figments of our imaginations, never-to-be in real life. I’m sure this was a lot like Napoleon Bonaparte’s own expectation that he’d conquer the world, something that proved to be beyond his grasp when it came down to the details.

Napoléon had promised his son, “It’s All Yours.”

Napoléon Francis Joseph Charles Bonaparte (aka Franz)

A little over two hundred years ago, Napoléon Francis Joseph Charles Bonaparte was born in the Palace of the Tuileries. It was assumed that he was destined to rule over a great empire. His mother was the Empress Marie Louise, a daughter of the Emperor of Austria. She was his father’s second wife, after he had divorced the Empress Joséphine.

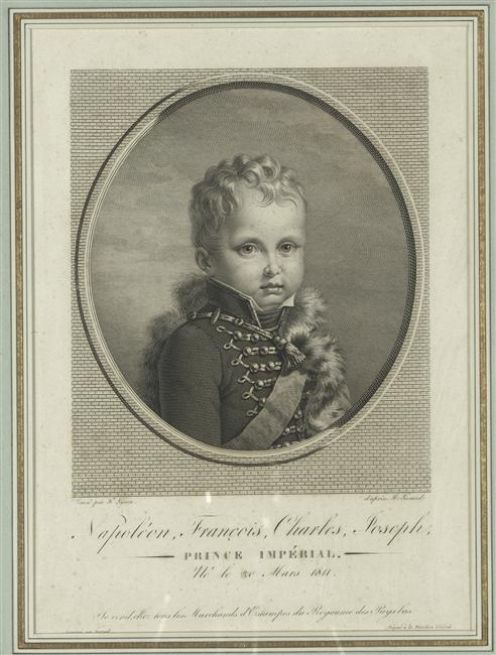

The boy’s birth on March 20, 1811 was announced by the roaring salute of many guns. At the time, his birth was a great joy to the French nation, as well as his parents. So you would think that historically his life would be as well-known as that of his father. However, this was not meant to be.

He was given the title of King of Rome, and his christening was a stately ceremony at the Cathedral of Notre Dame. It seemed as though he had a great future before him. It is a recorded fact that his father adored him, often spent time playing and talking with him as an infant. A doting father is not generally something most of us would think of when it comes to the Napoléon we’ve known through the retelling of history.

Yet, in the end he grew up without a mother’s love or a father’s care. His short life was pitifully lonely. His early death was a relief to most of the people. The few who thought of his existence at all have all passed away, and his name is scarcely mentioned in the teaching of history.

Napoléon Bonaparte’s son, who was called “Franz.”

The Education of Napoléon’s Son

When Napoléon François Joseph Charles Bonaparte was a toddler, his father, Napoléon, was at the height of his power. Everyone thought that the little King of Rome, as his baby son was officially called, was sure to succeed him on the throne of France. When Franz was only two and a half years old, his education was begun. He was given lessons almost before his baby lips could repeat the words that were taught him. It’s been claimed that at the age of three, he was fluent in French as any grown up. It was said that by the age of nine, rather than having a child s vocabulary, he was able to converse with ease on an adult level. He later learned German, Italian, Greek, and Latin.

His father was determined that he should be well prepared for the great place in history that he was to fill. But, before the prince was three years old, Napoléon had been defeated by the bitter cold of the Russian winter. All the countries in Europe had combined and conspired against him. He had fought and lost the Great Battle of the Nations at Leipzig. Even then, he might have kept his throne, if he had promised to be content with the kingdom of France, but this he refused to do so, ended up having everything was taken from him. The legacy of Franz’s father would prove to be his most difficult lesson of all.

The education of Napolean’s son Franz was a serious undertaking.

The Destiny of Franz — Napoleon II

As the armies of the allies who had defeated the Emperor neared Paris, Marie Louise fled from the city, taking the young King of Rome with her. When his mother first fled with him from Paris, they had to leave most of their possessions behind. Being a child, Franz thought that Louis XVIII had stolen his toys. The toys were later forwarded, but all Napoléonic symbols which were decorated on every toy, had been stripped from them on orders of his maternal grandfather.

Napoléon never again saw the son of whom he was so proud and whom he loved so dearly. Napoléon, of course, was sent into exile on the Island of Elba in the Mediterranean, from which he would later escape. Marie Louise who did not care for her husband any longer, made no effort to go to him, despite his loving pleas and commands that she do so. She was quite content to obey her father’s command that she should give up on her marriage and come home. She agreed, too, to give up the title of empress, and was made Duchess of Parma and two other small Italian states.

The title of King of Rome was taken from her son, and it was agreed that he was to succeed his mother, as Duke of Parama. His mother’s family wanted him to forget his French blood and his father. In time, however, he would rebel and later say:

“If France called me, I would come.”

All of this was in 1814, and the next year it seemed for a time, as if he might be emperor of the French after all. Napoléon escaped from Elba. He gathered a great army as he went and marched through France to Paris and turned out Louis XVIIII, the Bourbon king whom the allies had placed on the throne.

The boy all of France chose to forget.

Denied His Place in History

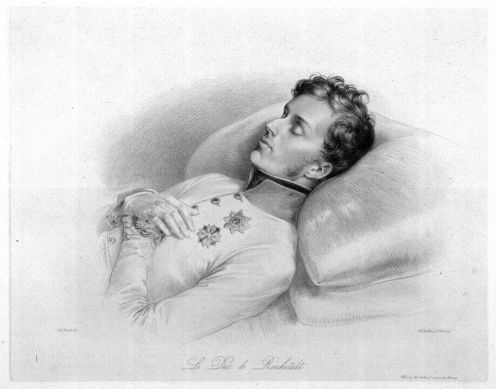

But, the Emperor’s second reign lasted such a short period of time that it is called “The Hundred Days.” Napoléon’s defeat at Waterloo put an end to it forever, and lost for his son even his small dukedom. For after Napoléon had been banished to St. Helena, the little boy was given the title of Duke of Reichstadt by his grandfather. It was decided that he should never rule.

Meanwhile, his father continued to dictate specific instructions to his young son Napoléon II. Even though he’d named his son as his successor when he abdicated, no one was willing to recognize him as legitimate to the throne of France. This was despite the fact that at the time most French peasant households had pictures of him on their walls. By this time, Marie Louise had gone to live in her duchy of Parma, but she did not take the little duke with her. From this time onward, he became a pawn in the game of European politics.

These efforts only made the great powers of Europe the more determined that no son of Napoléon should ever rule. Sometimes the great Austrian minister Metternich put forward his claims, and the other malcontents in Italy and in France used his name to stir up trouble. In November 1816, Marie Louise was informed that her son could not succeed to the duchy of Para. As he was not to succeed her, it was thought better that he should be left in Vienna with his grandfather, who undertook his education. His mother would only see him one more time, on his deathbed.

The Rest of Franz’s Short Life

He was brought up as an Austrian subject, instead of a French prince, and so all his French attendants were sent away. Even his nurse was eventually sent away. He was placed in the care of an Austrian gentleman, named Count Moritz von Dietrischtein, who was called his governor.

He was still so young that it was hoped that once he was surrounded by Germans, that he would forget all he had been told about his father. However, he never did forget who his father was. Perhaps, it was because he had some faint recollection of the man who played with him in the old days in France. He certainly remembered the stories his nurse had told him of his father’s greatness. It was reported that he grew up to love his memory and liked to think of him.

Later, his many tutors found him a difficult pupil, especially at first. He was about ten years old when his father died. He was very obstinate and he did not wish to speak German. There were many outbursts of temper to be subdued. Happily, however, he became much attached and fond of Count Dietrishstein, who was a very kind man. He treated him with great wisdom and affection.

Young Franz would grow to be a little over six feet tall at the age of seventeen. As much as others wished him to not be like his father, he shared many mannerisms. In anger, he shared a look that Napoléon was famous for, and was a constant reminder to the Austrians of his father. Additionally, he was known to have walked just like his father, often with his hands behind his back when thinking, walking in a circle, with his head down. He admired his father so much that he was delighted when he learned that his grandfather wished him to become a soldier. It was later another great day for him when he got his first uniform, though he was only made a corporal, for his tutors thought it better that he should be advanced slowly.

Learning to be a soldier was Franz Bonaparte’s strongest wish.

Franz Will Face His Own Waterloo

He was a clever boy, but lazy, and promotion was held out as a reward for diligence in his studies. No pains were spared to provide him with good teachers and to train him to be not only a good soldier, but also great man. His youth though wasn’t a pleasant one, as he was seldom allowed outside the palace grounds, and could never be alone. There were only a handful of theatre or battalion regiment practices that he was able to attend under supervision.

The year before he died, it’s speculated that this lonely boy did know love, or at least infatuation. He secretly met a ballerina at a theatre one night. She invited him to her dressing room after her performance. Her name was Franziska (Fanny) Elssler, and she was just one year older than him.

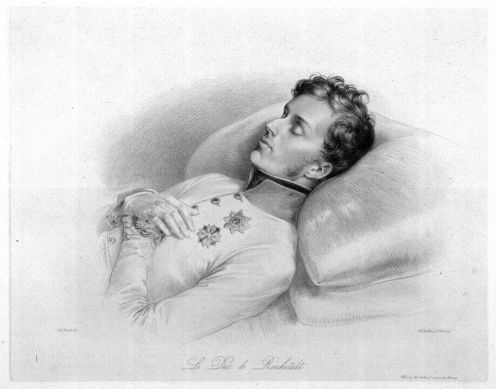

He was carefully taught his profession. All the soldiers were said to have looked forward to the time when he would command them, and perhaps lead them to victory. But their hopes were not to be realized, for already his days were numbered. In the spring of 1832, he fell ill with tuberculosis, and by July 22nd of that year, he was dead. When news of his death was heard in France, it caused but little mention. He was only twenty-one years old.

While much has been written about his father, and even his mother — there are very few references and details about the boy who might have been King of France — had history played out a different hand. He has been referred to in history books as the “the lifelong captive (but very much loved) of Habsburg empire.” Finally facing his own personal Waterloo in death, there was no denying his fate — he could not escape being a mostly forgotten footnote in history.

It’s seems almost ironic that all the hopes that Napoléon Bonaparte and others had invested in his son, were not what was to be his legacy. Rather what has remained instead is Napoléon Civil Code concepts, Napoléon’s sale of the Louisiana Territory, and his defeat at Waterloo. Seems sort of prophetic that Napoléon himself said:

“There is no immortality, but the memory that is left in the minds of men.”

Perhaps the most ironic part of the tale of the sad life of Napoléon François Joseph Charles Bonaparte, is another quote, that of his grandfather, who upon learning of his death was reported to have said:

“It was best for both of them that he was dead. Very sad life.”

Napoléon François Joseph Charles Bonaparte

Recent Comments