Nathaniel Pryor: the Unsung Veteran of the Battle of New Orleans

March 4, 2015 in American History, general history, History, Louisiana History, Native American History

Among the American soldiers in the Battle of New Orleans, Capt. Nathaniel Pryor is one whose name shows up in no histories of that great battle. Oddly, Capt. Pryor, who served in the 44th Infantry under Col. George T. Ross, never received his rightful credit for participating, or even any special notice by Gen. Andrew Jackson. Pryor, of Virginia and Kentucky, is better known as one of the men who accompanied Meriwether Lewis and George Clark on their exploratory expedition of the Louisiana Purchase lands to the Pacific Ocean and back in 1804-1806.

He had joined the 44th Infantry Regiment August 30, 1813, as a first lieutenant, but did not go to New Orleans until September of that year. By Oct.1, 1814, he was promoted to captain, the highest post he would attain before he was honorably discharged June 15, 1815.

During the Battle of New Orleans, Capt. Pryor fought in the center of Line Jackson alongside his brothers, James Pryor and Robert Lewis Pryor, who had come to New Orleans with the Kentucky soldiers. They were placed alongside sharpshooters from Kentucky and Tennessee. Other Pryor relatives also were there, including his cousins Nathaniel Floyd, Thomas Floyd Smith and William Floyd Turley.

Pryor came to New Orleans late in 1813 from St. Louis, where he had earlier served as a special agent working for his old leader, Missouri Territory Governor Clark. He had done a secretive spying mission for Clark on Tecumseh’s camp at Prophetstown in 1811, and his report alerted Clark and Indiana Governor William Henry Harrison about the rapid advances Tecumseh was making in gathering various tribes to his cause against the white settlers. Pryor’s report was directly responsible for spurring Harrison and US forces to attack the Indians at the Battle of Tippecanoe in Indiana, when they burned Prophetstown to the ground in November 1811. Although Tecumseh was absent from that battle and soon rallied back, Harrison regarded the conflict as a success, and his name was so tied to it that Tippecanoe was used as a campaign slogan in his later successful bid for the US presidency.

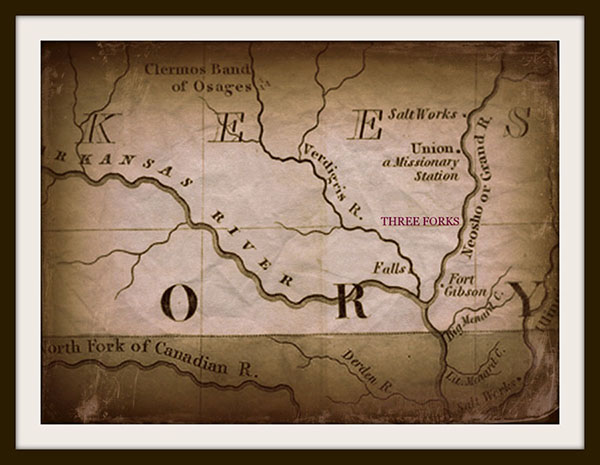

After his discharge from the 44th, Pryor went to the Mississippi River trading center of Arkansas Post, where he operated a business with Samuel Richards for a time. After he won a permit to trade with the Osage Nation in 1817, he proceeded up the Arkansas River to the Three Forks area of the Verdigris, Neosho, and Arkansas watershed confluence, and set up a small trading post just above the mouth of the Verdigris River.

While at the Three Forks, he became friends with a fellow Indian trader, the legendary Sam Houston, during Houston’s days with the Cherokees at Wigwam Neosho. When an opening came up at the Indian Agency near Ft. Gibson, Pryor asked Houston to recommend him for the position. Houston sent letters to both Secretary of War Jonathan H. Eaton, and his old friend, Jackson, then the president of the United States.

On Dec. 15, 1830, Houston wrote from his home at the Wigwam Neosho, almost directly across from Ft. Gibson. He implored both Eaton and President Jackson to recognize Pryor’s past service to the country by awarding him the appointment as sub agent for the Osage Nation.

He reminded Jackson that Pryor served under him at the Battle of New Orleans as a captain in the 44th Regiment: “…a ‘braver’ man never fought under the wings of your Eagle. He has done more to tame and pacificate the dispositions of the Osages to the whites, and surrounding Tribes of Indians than all other men, and has done more in promoting the authority of the U. States and compelling the Osages to comply with demands from Colonel Arbuckle than any person could have supposed.”

“Capt. Pryor is a man of amiable character and disposition__of fine sense strict honor__perfectly temperate, in his habits__and unremitting in his attention to business,” wrote Houston.

Houston added on his last visit to Washington, D.C., Sec. of War Eaton had assured him that Pryor’s claim for the subagency post with the Osage Nation would be considered, yet another man was appointed, and Pryor was passed by.

“He (Pryor) is poor, having been twice robbed by Indians of furs and merchandise some ten years since…” wrote Houston. He stressed that the claim of Pryor to the subagency appointment was “paramount to those of any man within my knowledge, I can not withhold a just tribute of regard.”

Others also were struck by Capt. Pryor’s situation. General Thomas James, who met Pryor in August 1821 along the Arkansas near the present-day site of Tulsa, Oklahoma, was quite impressed by him, and disgusted by his poor recompense for past service.

“On the reduction of army after the war, he was discharged to make way for some parlor soldier and sunshine patriot, and turned out in his old age upon the ‘world’s wide common’! I found him among the Osages, with whom he had taken refuge from his country’s ingratitude and was living among them as one of their tribe, where he may yet be, unless death has discharged the debt his country owed him,” wrote James in his autobiographical book “Three Years Among the Indians and Mexicans.”

Pryor finally was appointed sub agent for the Osages of the Verdigris on May 7, 1831. The man who had been appointed sub agent for all of the Osage Nation, D.D. McNair, was struck and killed by lightning while riding near his post on Jun 2, 1831. Pryor, who had been ill since December 1830, died June 10, 1831, at age 59 at the Union Mission Indian school located on the Neosho River about 25 miles north of the Three Forks junction.

Although Capt. Pryor never received proper honors from the US government for the roles he played in the Lewis and Clark expedition and Battle of New Orleans, his life was its own reward. He became a part of history the minute he became the first man to sign up for the Corps of Discovery. His brave spirit lives on in his namesake town of Pryor, located in northeastern Oklahoma in Mayes County, and his grave is nearby not far from Pryor Creek.

Money and fame never found Pryor, but he had been wealthy with adventures. He had traveled cross-country into the unknown to help forge a path on a dangerous trip of discovery; successfully spied on Tecumseh and his warring Indian tribes shortly before the War of 1812; nearly been burned alive in his home near Dubuque, Iowa, before escaping and fleeing hostile Indians by successfully jumping across ice floes in the Mississippi River; fought the British and helped win the Battle of New Orleans; pushed to the edges of the southwestern frontier on an expedition to Santa Fe in the early 1820s, and became a friend to the warring Osage Nation of Arkansas Territory. Few have led such a vibrant, action-filled life. Remarkably, he had gone through most of it partially disabled, as during the Lewis and Clark trip, he injured one of his shoulders so severely he had only limited use of one arm for the rest of his life.

Related Articles

Eyewitness Report of Jean Laffite at Chalmette Battlefield

The First Battle of New Orleans Poem

Commemoration of a Hero: Jean Laffite at the Battle of New Orleans.

Recent Comments