Andrew Jackson by Thomas Sully From Wikimedia Commons

Andrew Jackson resented mightily the fine imposed on him by Judge Dominick Hall in New Orleans in 1815 for contempt of court. At the very end of his life, with death approaching, Jackson campaigned for the return of the thousand dollar fine through an act of Congress, and his efforts were rewarded. “He viewed the return of his fine as a larger statement about the legitimacy of violating the constitution and civil liberties in times of national emergency.” (Warshauer, p.6) That is the crux of the problem presented in Matthew Warshauer’s Andrew Jackson and the Politics of Martial Law: Is it ever all right to violate the constitution? Did Andrew Jackson set a precedent that it was, a precedent later followed by Abraham Lincoln and every wartime president since?

The fine was levied by the Federal District Court in 1815. It was refunded to Jackson by Congress in 1844. But did this refund really serve as a justification of martial law? Or was it just a sign of appreciation for a dying former president and national war hero?

The term “martial law” was at one time a synonym to “military law” and used to describe the legal tradition of absolute law – one characterized by a lack of civil liberties – that applied to those who served in the military while they were in active service. Only later, after the Congressional debates concerning the refunding of the Jackson fine, did “martial law” come to mean giving the military absolute authority over civilians in times of emergency. (Warshauer, p. 17).

Nationalism, according to Warshauser, was the force that allowed the constitutional limits on military authority to be breached, not just in the case of Andrew Jackson, but for every member of the executive branch since who has invoked emergency powers:

To many, Jackson represented the pinnacle of American nationalism. The Battle of New Orleans had invested him with the highest claims of patriotism and devotion to country… Jackson’s understanding of his nationalist appeal is one of the items that made him a formidable politician and president. Subsequent presidents have embraced the same political use of nationalism. Lincoln focused on the sanctity of the Union during the Civil War and … embraced martial law. Consider also the nationalism fomented by Franklin Roosevelt in the midst of the Great Depression. He utilized the overwhelming nationalist support of the 1936 election to challenge the Supreme Court’s threats to his New Deal legislation. … [E]ngagement in World War II was impossible without nationalist sentiment … in the form of … Pearl Harbor…Similarly, George W. Bush could not possibly have engaged in a war against Iraq … or curtailed civil liberties with the Patriot Act without the nationalism spawned by [9/11]. (Warshauer p. 18)

Did Andrew Jackson really invent American nationalism? Did it not exist before that moment in 1814 when he arrived in New Orleans? When exactly did American nationalism come into being? And what does the term mean in this context? Is it just a another word for patriotism? Or does it mean loyalty to one’s nation of origin?

It was not that sense of nationalism that led to the American Revolution. Abigail Adams, writing to her husband John, on November 12, 1775 referred to the common origin of the Americans and the British: “Let us separate, they are unworthy to be our Brethren. Let us renounce them and instead of supplications as formerly for their prosperity and happiness, Let us beseech the almighty to blast their counsels and bring to Nought all their devices.” Notice that there is no question that the British were the brethren of the American colonists. It was just that they weren’t worthy! If on national grounds alone, the Americans and the British were one people. But the American colonists’ insistence on the civil liberties secured to all Englishmen applying also to themselves was the reason for the separation. If anything, this was anti-nationalism. Civil liberties trumped national unity.

Andrew Jackson, while still a minor, served in the Revolutionary War. He defied the British, his brethren, at the risk of his life. When exactly did he become a nationalist? Could it be when he entered the City of New Orleans and realized that he would need to get Edward Livingston to translate everything he said to French before he could address the people of the city and hope to be understood?

To an ill-educated boy from the rural south, New Orleans was cosmopolitan and foreign. It was filled with people who had just recently been French and only a little earlier had belonged to Spain, and it was more foreign by far than the invading British forces! “Concerns over spies and dissent within the largely foreign city prompted Jackson to proclaim martial law.” (Warshauer p. 19). Jackson did not trust the people of New Orleans precisely because they were not his brethren!

While Jackson’s feelings of being outnumbered by foreigners in a city whose defense was chiefly his responsibility might be quite understandable, both retrospectively in 1842 when the congressional refund debates began and maybe even prospectively in 1814, the situation he was placed in came about through the extra-constitutional machinations of Thomas Jefferson in 1803.

There was no provision in the constitution for new territories –and the human population that lived within them– to be bought and sold at taxpayer expense . The provision for new states to be brought into the Union presupposed that the majority of those living there would petition to join of their own free will. And it was probably presumed, at the time of the writing, that these new people would be brethren who had colonised large wilderness areas and had come to outnumber the natives who were there first.

But Anglo-Americans in New Orleans were outnumbered by French Creoles and Cajuns, free blacks, Spanish merchants, Catholic clergymen and nuns, both French and Spanish, whose oath of loyalty was to the Pope before any State or monarch, and any number of other “foreigners” or at the very least, people who sounded and looked foreign, even though they were now legally American citizens, Louisiana having just joined the Union as a state in 1811.

Would Andrew Jackson ever have considered imposing martial law if he had been stationed in a state such as South Carolina during the beginning of the War of 1812? There, it was the local free white males who had failed to obey the orders of their governor, Joseph Alston, thereby leaving the state without a defense force during the beginning of the war. A writ of habeas corpus had been issued to free deserters from the militia, because the possibility of dying of malaria was felt to be much more real than any just-declared war against Britain.

The unusual state of affairs in New Orleans due to the Louisiana Purchase is one of the factors that led to Jackson’s decision to invoke martial law. He did not trust the citizens of New Orleans, because they seemed foreign. It is not, however, something that comes into the legal argument that was derived from this precedent, which was later applied against his own brethren by President Lincoln in the context of a civil war.

Andrew Jackson was not, in fact, the first American general to attempt to impose martial law on New Orleans, although he was the first to make it stick as a legal precedent. The first to impose martial law in American held New Orleans was General James Wilkinson, who was also, at the time, the Governor of Louisiana Territory, and his purpose in so doing was not to repel a foreign invasion, but to apprehend and disenfranchise Aaron Burr and his friends Erich Bollman and Samuel Swartwout, whom he accused of plotting to take over the Western territories and separate them from the United States.

At the time, Edward Livingston, also a friend of Burr’s, had just barely escaped being summarily arrested as well. Writs of habeas corpus were ignored and the attorneys presenting them threatened with arrest. Deprived of the right to counsel, the prisoners were transported by the military branch of the government and kept without right to trial. As it happens, James Wilkinson had been a Spanish spy, and it was in his capacity of an agent of Spain that he acted to repel Aaron Burr’s attempt to filibuster his way through Texas and Mexico. Which is a reminder that a person does not necessarily need to be a foreigner to serve as both a spy and a traitor.

Andrew Jackson was aware of these past events, for he, too, just like Bollman and Swartwout and Edward Livingston, was a good friend of Aaron Burr and a supporter of his would-be venture against Spanish held Mexico. He stood by Burr during the treason trial in Richmond, and he was aware of the Supreme Court decision in Ex Parte Swartwout and Ex Parte Bollman that stated that the right to habeas corpus may not be infringed by the executive branch unless Congress passed a law suspending the writ of habeas corpus. Thomas Jefferson had wanted to pass such a measure through Congress in his eagerness to foil Burr, but Congress did not grant his wishes.

So here was Andrew Jackson, like James Wilkinson before him, suddenly declaring an emergency and suspending the writ of habeas corpus. What would be the right course of action for anyone disagreeing with Andrew Jackson’s imposition of martial law? To file a motion for a writ of habeas corpus? It was exactly the right so to do that had been suspended. To openly rebel against the armed forces of the United States? Even if successful, that would open anyone so doing to a charge of treason.

The right to a writ of habeas corpus and to be free of martial law is one of those things that get hammered out in a court of law after the fact. They cannot under normal circumstances be resolved in the heat of the moment. Even in Ex Parte Bollman first the right to habeas corpus was suspended, and only later was this ruled to be unconstitutional.

One difference between the two cases was that the United States was not in fact at war when James Wilkinson tried to suspend the writ, so that the Supreme Court was still sitting, and it was possible to appeal directly to the highest court on a question of jurisdiction, even if lower court judges were imprisoned for speaking up in New Orleans. But America was under siege in 1814, and in August of that year the capital had been burned by the British. Government buildings were still in shambles at the time of the Battle of New Orleans.

Before the Battle of New Orleans the pragmatics of the situation and the extreme gravity of the British threat allowed Jackson to do whatever he chose without real resistance. Any checks and balances to his actions of a constitutional nature could only come too late and after the fact. This meant that restitution and/or a fine could be levied against Jackson later, but nobody could get an injunction to prevent him from doing whatever he chose to do right then.

Jackson was fully aware of this state of affairs. He asked the counsel of two legal advisors before he took this step:

Jackson’s advisors, Edward Livingston and Abner Duncan, ultimately concluded that martial law suspended all civil functions and placed every citizen under military control. The lawyers disagreed, however, on the legality of the proclamation. Livingston believed that it was “unknown to the Constitution or laws of the U.S.”… (Warshauer p.23)

On December 16, 1814 Andrew Jackson issued his proclamation imposing martial law on the City of New Orleans. “All who entered or exited the city were to report to the Adjutant General’s office. Failure to do so resulted in arrest and interrogation. All vessels, boats and other crafts desiring to leave the city required a passport, either from the General or Commodore Daniel T. Patterson. All street lamps were ordered extinguished at 9:00 p.m., and anyone found after that hour without a pass was arrested as a spy. New Orleans was officially an armed camp and General Jackson the only authority.” (Warshauer p.24)

It was ironic that Daniel T. Patterson was given almost equal authority with Andrew Jackson, since if there was ever a British sympathizer in the city of New Orleans, he, rather than the French speaking populace, must surely have been guilty. It was after all Patterson who attacked the Baratarian privateers, destroying their base, and capturing their ships, when Jean Laffite informed him that the British were anchored off Mobile Point and about to attack Fort Bowyer and offered to help him fight the British. But Daniel T. Patterson was an American naval officer, and Jackson trusted him implicitly. There was nothing foreign about him.

Among other powers that Jackson summarily granted himself with this proclamation of martial law was the power to draft into the militia or impress into naval service any person and to confiscate property, which included fencing, the wood in the walls of “negro houses”, muskets and flints, and even bales of cotton. Nothing taken was paid for, though receipts acknowledging the confiscations were provided.

Every slave, horse, ox, and cart was requisitioned for military use, and the general authorized the enlistment of all Indians within the district to serve on the same footing as the militia. Mayor Nicholas Girod received orders to “search every house and Store in the City for muskets, Bayonets, Cartridge boxes, Spades, shovels, pick axes and hoes”…

From the point of view of second amendment rights, it seems interesting that arms were being confiscated from their owners, rather than the owners simply being enlisted in the militia and asked to bring along their own weapons in the service of their country. This does not seem like the well-regulated militia contemplated by the second amendment. Instead, arms were taken from the people who owned them and being redistributed to other people who were considered more trustworthy.

While all this conscription and confiscation was going on under the guise of martial law, the thing that truly saved the city came in the form of a donation freely given. Jean Laffite and his Baratarian artillery unit were eager to serve and happy to donate flints and powder and artillery – if only the General would allow them to enter the city! As there were not enough flints available in the city, this donation was indispensable. It was in grudging cooperation with the Baratarians that Jackson was able to win the Battle of New Orleans and with that the undying gratitude of the nation. The glorious battle culminating in an American victory on January 8, 1815 led to much rejoicing, including public displays in the the Place d’Armes in which Baratarians alongside other American volunteers marched proudly, and at a banquet for high ranking officials, Jean Laffite stood side by side with Andrew Jackson as an honored hero. And then… everything should have gone back to normal, only it didn’t.

The citizenry of New Orleans may have grumbled, but they were by and large accepting of Jackson’s actions imposing martial law prior to the Battle of New Orleans. Despite his suspicion of them, most did not want to submit to the British and did everything they could to support the defense of the city. It was only after the American victory and when rumors that a peace treaty had been signed began to circulate that people started to openly rebel and inquire as to why it was that in peacetime martial law had not yet been lifted. “Desertions and mutiny among American troops prompted even more arrests. No longer perceiving a threat to their city after the January 8 victory, the citizens of New Orleans demanded a return to their former lifestyles.” (Warshauer p.31)

Businesses had been neglected. All commerce had ceased. Families lost their breadwinner. All this was acceptable during the thick of war, but the sooner things went back to normal once the war was over, the less suffering to the citizenry. Jackson, however, held onto wartime measures without any compunction for the suffering he was inflicting, long after the danger from the enemy was past. He ordered deserters imprisoned, then shot. One man, Pvt. James Harding, who deserted to help his wife who had been evicted from their home, was granted a reprieve from execution only at the last moment. These deserters were not career military, but ordinary citizens who had been glad to serve their country when the help was needed, but who had obligations in civilian life that were now pressing. Many residents of New Orleans of French and Spanish origin who had been happy to serve in the thick of battle were now starting to ask the French and Spanish consuls to provide them with exemptions on the grounds that they were really French or Spanish citizens. Everything that had united the residents in defense against the enemy was now conspiring to separate them in light of the continued iron rule of Andrew Jackson’s martial law. (Warshauer pp. 32-33.)

In mid-February, more than a month after the British had retreated for good, boarded their ships and disappeared, Jackson attempted to scare the citizenry into obedience by saying that “the enemy is hovering around us and perhaps meditating an attack.” (Warshauer p.32). Rather like an incompetent parent conjuring up the bogeyman to get children to obey, Jackson needed an invisible enemy to keep the people of New Orleans in line.

On February 24 Governor Claiborne wrote to exiled Attorney General Stephen Marerceau: “I can no longer remain a Silent Spectator of the prostration of the Laws. – I therefore request you, Sir, without loss of time to repair to this city… and resume your official duties…. And on receiving any information of any attempt of the Military to seize the person of any Private Citizen, not actually in Military Service of the United States, you are specially instructed to take for his protection, and for avenging the Injured Laws of this State such measures as your knowledge of the laws will point out.” (Warshauer p.34)

On March 3, an article appeared in the Louisiana Courier signed anonymously by “A Citizen of Louisiana of French Origin”:

[I]t is high time the laws should resume their empire; that the citizens of this state should return to the full enjoyment of their rights; that in acknowledging that we are indebted to General Jackson for the preservation of our city and the defeat of the British, we do not feel much inclined, through gratitude, to sacrifice any of our privileges, and less than any other, that of expressing our opinion of the acts of his administration….

The article was penned by state senator Louis Louaillier, and one of the chief acts of the administration that he complained of was bringing citizens before military tribunals “a kind of institution held in abhorrence even in absolute governments.” Two days after the article appeared, Jackson had Louaillier arrested and warned that any person serving a writ of habeas corpus to free Louiaillier would also be imprisoned.

If Jackson wanted to prove himself a tyrant, then there could have been no better way to do it. A request for a writ of habeas corpus had in fact already been made before Federal Disrict Court Judge Dominick Hall. Hall, who had been appointed by none other than Thomas Jefferson in 1804. Hall equivocated momentarily on the issue of jurisdiction – was this a Federal or a State matter? – then granted the request. No sooner had Judge Hall granted the motion for a writ of habeas corpus, then Andrew Jackson had him arrested for “aiding and abetting and exciting mutiny within my camp.” In Jackson’s mind, the entire city of New Orleans was his camp and every citizen, from Federal Judges to state senators to the lowliest householder – was a soldier at his beck and call. (Warshauer pp.35-36)

And this might never have ended, if not for the arrival of an official notification on March 13 to Andrew Jackson of the ratification of the Treaty of Ghent.

Signing of the Treaty of Ghent

Wikimedia

But as soon as the treaty, which had already been signed on December 24, 1814, while the Battle of New Orleans was ongoing, by Ambassador John Quincy Adams for the Americans and by Admiral of the Fleet James Gambier, and that was ratified by the Prince Regent ( aka George IV) on January 30, 1815, was also ratified by the U.S. Senate on February 18, 1815, it was in fact the law of the land. There was only one problem: Jackson had not been told about it through proper channels. Yes, he’d heard about it. But not through official channels. And Andrew Jackson always went by the book.

As soon as Jackson received notification of the peace of Ghent being ratified by all parties, he revoked martial law and all the many prisoners were released, those exiled were allowed to come back to the city, and the case against Jackson was brought to court. United States v. Major General Andrew Jackson was what it was called, Judge Hall presided, and when all the legal arguments were settled Andrew Jackson was found in contempt of court and fined one thousand dollars, which, without admitting any wrongdoing, he paid.

Jackson was not forced to spend a single day in prison, despite the many he imprisoned. He was not forced to undergo any corporal punishment such as a flogging that many an impressed sailor had to undergo, he was not court martialed, nor executed summarily like the men had shot, he was not stripped of rank and dignity, he was not forced to go into exile like Aaron Burr after his acquittal for treason, and he did not lose his military pension. For violating the most important provisions of the constitution, including the first and second amendments, while in the pay of the United States, it was a mere slap on the hand.

But to Jackson it rankled, and so he hoped that one day he would be vindicated. In fact, he has been, not merely by the Congressional award in 1844 of his fine with interest, but by the political reality and even by the narrative that is told today by historians.

The argument on either side has always been a question of constitutionality versus necessity, as first formulated by Edward Livingston. Those who felt Jackson’s imposition of martial law was not constitutional to this very day seem to argue that it was nevertheless necessary. Matthew Warshauer is certainly one example: “Can one violate civil liberties if doing so saves the government that provides those civil liberties? …However much one might like to disdain Jackson for military rule, he did in fact save the city in a victory that was unprecedented and perhaps impossible without martial law.” (Warshauer pp. 44-45.)

Do governments provide civil liberties? Or do the best of them merely stand aside and not infringe on civil liberties that the people are already endowed with? The declaration of independence seems to argue for the latter and to deny the former. Is the rise of American nationalism referred to earlier in the text by Warshauer in fact just a rise of statism, having nothing to do with nationality or patriotism, but with the state’s supremacy over individual citizens? And did Jackson win the Battle of New Orleans because he imposed martial law or despite his unpopular and unconstitutional wielding of absolute power? This depends on whether one acknowledges the contributions of Jean Laffite and the Baratarians.

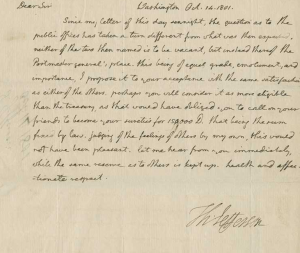

James Wilkinson — What a real spy looks like

Warshauer distinguishes between unfortunate excesses to be deplored — the jailing of a Federal judge and a state senator in time of peace for expressing opinions or issuing writs — and the need for thwarting spies and saboteurs. But the belief that martial law is a good deterrent against spies or saboteurs (today known as terrorists) is misguided. In a war against the British, the enemy looked and acted just like us. It would not have been possible to tell who was a British sympathizer based on their place of origin or the accent they used when they spoke, the clothes they wore, their twirling mustaches or their overall manner. The man issuing passes was just as likely to be a British sympathizer as the lowliest citizen with a foreign accent. Foreign-sounding names like Louaillier and Laffite did not necessarily imply lack of loyalty, when real spies during that era had names like Arnold or Wilkinson, and British sympathizers were often called something like Patterson. The color of a person’s skin meant nothing when real spies — whether for England or Spain — had the rosy complexions and the clean shaven faces of Englishmen. You simply could not look at someone and tell that he was a spy, and while there were in fact spies (it was not all paranoia), no spy was ever caught thanks to the unconstitutional measures imposed by martial law.

It is true that when Andrew Jackson entered the city in December of 1814, there was a spirit of disaffection between the people of New Orleans and their American-imposed government, but it was not because they were sympathetic to the British. On the contrary, they hated the British fiercely, and it was only to the extent that the Americans behaved like the British that this disaffection carried over. Tax collectors and revenuers, men of the Revenue Cutter Service, were thwarting the commerce of the United States, first under the color of the Embargo Act, and later the Non-Intercourse Act, laws which were in fact unconstitutional and contrary to the spirit of the American revolution. Governor Claiborne’s real difficulty was in getting rid of smugglers and privateers who fought the British and then sold their goods to the citizens of New Orleans at a fraction of the cost. This was galling both to the tax collector and to the American merchants who had bought British goods at full price despite the embargo, but it was in fact a service to nation in its fight against the British. The crux of the disagreement between the people of New Orleans and their state Governor and with Commodore Patterson of the Federal government was who should pay for waging war. But to suggest that the citizens of New Orleans would not have fought to defend their city from the British unless they were conscripted under Jackson’s martial law is deeply misleading and offensive.

Who fights better, conscripts or volunteers? You can lead a man to battle, but can you force him to fight? How helpful were the bales of cotton, the fencing and the muskets and cartridges that were confiscated, when not placed in the willing hands of their owners to do battle for New Orleans? How many men who wanted to serve were alienated by being forced to serve? How many “foreigners” were sacrificed so that native born double dealers like Daniel Patterson could make money off stolen goods from Barataria? Wasn’t the Battle of New Orleans won largely through the generosity of Jean Laffite who donated flints and powder, artillery and trained men, who had learned professional shooting as privateers and could make important contributions to both tactics and strategic planning? Didn’t Andrew Jackson himself commend the dedication of Dominique You and Renato Beluche?

We don’t have to question the good intentions of Andrew Jackson to note that what he did was wrong. The excesses under martial law that we deplore are the natural and inevitable consequence of absolute power, and even the most well-intentioned man will fall into them as a result of wielding that power. When President Madison asked that Congress approve a declaration of war against Britain, it was impressment of sailors by the British that served as a pretext. Can impressment of sailors by Andrew Jackson be justified as a response to that? Or was the willing contribution of privateers to the success of the Battle of New Orleans the real reason the war was won?

References

Davis, William C. 2005. The Pirates Laffite: The Treacherous World of the Corsairs of the Gulf. Harcourt.

Hunt, Charles Havens. 1864. Life of Edward Livingston. D. Appleton and Co.: New York.

Kennedy, Roger. 1999. Burr, Hamilton and Jefferson: A Study in Character. Oxford University Press.

Warshauer, Matthew. 2006. Andrew Jackson and the Politics of Martial Law. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

http://www.revolutionary-war-and-beyond.com/abigail-adams-reveals-anger-toward-great-britain.html

http://www.historiaobscura.com/commemoration-of-a-hero-jean-laffite-and-the-battle-of-new-orleans/

Recent Comments