Commemoration of a Hero: Jean Laffite and the Battle of New Orleans

March 6, 2014 in American History, Caribbean History, general history, History, Louisiana History

A “Buccaneer” scene from the Battle of New Orleans, with Yul Brynner as Jean Laffite, at Battery No. 3.

Almost 200 years ago, privateer-smuggler Jean Laffite became a hero because he did something most people wouldn’t have done: in the face of extreme adversity, he had helped save New Orleans for the Americans, even though United States officers had destroyed his home base and seized his property a few months earlier.

Sometimes incorrectly regarded as a pirate, Laffite and his Baratarian associates were actually privateers sanctioned by the Patriot regime of Carthagena to prey on Royalist Spanish shipping in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean. They smuggled prize goods past customs at New Orleans through their base ports of both Cat Island and Grande Terre, providing low-priced goods to the populace through both auctions and other sales.

“Though proscribed by my adoptive country, I will never let slip any occasion of serving her, or of proving that she has never ceased to be dear to me” wrote Laffite to Louisiana legislator Jean Blanque on Sept. 4, 1814, in an enclosure that contained British letters he had received from Commodore Nicholas Lockyer of HMS Sophie the day before at Grande Terre. Laffite also said the British represented to him a way to free his brother Pierre from prison. Pierre had been incarcerated at the Cabildo in New Orleans since early summer 1814 after being arrested on a grand jury indictment.

Lockyer had tried to bribe Laffite to aid the British in their plans to seize New Orleans, but Jean had stalled for time about a reply, so he could advise the New Orleans authorities about the imminent threat. Lockyer told his superior, Capt. William Henry Percy, that his mission to secure ships and assistance from Laffite had met with “ill success.”

Blanque gave the letters, including Laffite’s, to Louisiana Governor W.C.C. Claiborne. Perversely, Claiborne’s advisory council decided to allow US Commodore Daniel Todd Patterson and Col. George Ross to proceed with a raid on Grande Terre. On the morning of Sept. 16, US ships and gunboats under the direction of Patterson and Ross blew up Laffite’s home and Grande Terre to bits, confiscated nine ships in the harbor, and all the goods they could find, from wine to German linen to exotic spices. They also pursued fleeing Baratarians, and imprisoned some 80 of them, including Dominique You, who had made sure that none of the Baratarians fired on the American vessels, per Laffite’s instructions.

Almost as soon as the British letters arrived in New Orleans, somehow Pierre escaped from jail and quickly rejoined his brother at Grande Terre, where he, too, wrote a letter to Claiborne to offer allegiance to the US.

Jean and his brother Pierre then had left Grande Terre to hide out at the LaBranche plantation on the German Coast, slightly upriver from New Orleans. They would remain fugitives until a short while after Gen. Andrew Jackson’s arrival at New Orleans in December. Jean was subject to arrest on sight following the raid.

So what did Laffite do right before the raid, and afterward? Here is what he says he did, in his own words, in a letter to President James Madison written Dec. 27, 1815:

“I beg to … to state a few facts which are not generally known in this part of the union, and in the mean time solicit the recommendation of your Excellency near the honourable Secretary of the treasury of the U.S., whose decision (restitution of the seized ships and items in the Patterson raid) could but be in my favour, if he only was well acquainted with my disinterested conduct during the last attempt of the Britannic forces on Louisiana. At the epoch that State was threatened of an invasion, I disregarded any other consideration which did not tend to its safety, and therefore retained my vessels at Barataria inspite of the representations of my officers who were for making sail for Carthagena, as soon as they were informed that an expedition was preparing in New Orleans to come against us.

“For my part I conceived that nothing else but disconfidence in me could induce the authorities of the State to proceed with so much severity at a time that I had not only offered my services but likewise acquainting (sic) them with the projects of the enemy and expecting instructions which were promised to me. I permitted my officers and crews to secure what was their own, assuring them that if my property should be seized I had not the least apprehension of the equity of the U.S. once they would be convinced of the sincerity of my conduct.

“My view in preventing the departure of my vessels was in order to retain about four hundred skillful artillerists in the country which could but be of the utmost importance in its defense. When the aforesaid expedition arrived I abandoned all I possessed in its power, and retired with all my crews in the marshes, a few miles above New Orleans, and invited the inhabitants of the City and its environs to meet at Mr. LaBranche’s where I acquainted them wih the nature of the danger which was not far off…a fews days after a proclamation of the Governor of the State permitted us to join the army which was organizing for the defense of the country.

“The country is safe and I claim no merit for having, like all inhabitants of the State, cooperated in its welfare, in this my conduct has been dictated by the impulse of my proper sentiments; But I claim the equity of the Government of the U.S. upon which I have always relied for the restitution of at least that portion of my property which will not deprive the treasury of the U.S. of any of its own funds.

Signed Jn Laffite”

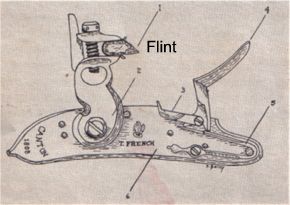

The interesting thing about Jean’s letter to the President is he considered the aid of his veteran artillery personnel to be the most important contribution to the defense of New Orleans, and he says nothing at all about what was truly his most valuable aid to the Americans_the supply of some 7,500 desperately needed gun flints, flints which Gen. Andrew Jackson himself said later were the only ones he had during the battles against the British at Chalmette. Indeed, in a letter to a friend in 1827, Gen. Jackson flat out stated that the Laffite cache was “solely the supply of flints for all my militia and if it had not been for this providential aid the country must have fallen.”

For those unfamiliar with firearms of that era, most were muskets, fowling pieces, some Kentucky long rifles, and a variety of pistols, all with the flintlock firing mechanism. Flintlocks require small specially shaped squares of flint to spark the charge into the gunpowder to fire the lead shot. Without a flint, the weapon is useless save as a club, and indeed many pistols of the time were fortified with brass wrap-arounds on the stock to make them heavier towards that end. If Jackson’s men had no flints, they would have only had cannons, swords, knives, bayonets and guerilla style hand-to-hand fighting to fall back on, whereas the British were fully supplied with flints and firearms. The British would have easily routed Jackson during the Battle of New Orleans if Jackson’s troops could not have fired back at them. Jackson was correct in his assessment of the value of those flints, he was not exaggerating at all. Sometimes the smallest things can make the biggest impacts.

It is not known exactly when Laffite delivered the flints to Jackson, but it was sometime after Dec. 22, as the Americans had insufficient flints during the night raid on the British camp on Dec. 23, and were seizing British weapons in that event.

On Dec. 22, Jackson sent Jean Laffite to the Temple area near Little Lake Salvador to assist Major Reynolds with blocking the bayous there, plus setting up fortifications on the ancient Indian shell mound area. He told Jean he wanted him back at Chalmette as soon as possible. On his way back to Jackson’s Line, Laffite and some of his men must have picked up the kegs of flints from a Laffite warehouse in New Orleans, or the immediate vicinity, as the flints were soon being distributed on Jackson’s line.

The combination of Laffite’s flints, the expert cannoneers Dominique You and Renato Beluche, Jackson’s tactical skills and leadership, and the logistical combined nightmare of the swampy ground and unusually cold weather proved overwhelmingly devastating for the British. The Battle of New Orleans was an extremely horrible defeat for them, as at the conclusion, the ground in front of Jackson’s Line at the Rodriguez Canal was called a literal “red sea” of the dead and dying English troops and officers.

The most prominent history of the New Orleans campaign is

”Historical Memoir of the War in West Florida and Louisiana” written by Jean Laffite’s friend and Jackson engineer Arsene Lacarriere Latour. There were some contemporary histories written by British participants in the New Orleans campaign. None of these say anything about receiving any type of assistance whatsoever from Jean Laffite, although British historian Tim Pickles of New Orleans makes the preposterous and undocumented claim that only Jean could have led the British through Lake Borgne to the Bayou Bienvenu. However, neither Jean nor Pierre were anywhere near that vicinity on Dec. 16, 1814. Some Spanish fishermen who knew those bayous thoroughly were there, because that’s where they lived. A few of them, named in Latour’s history, were the ones who aided the British, not either Laffite. History is the art of interpretation of the past, but facts are facts. Jean did not tell Lockyer he would help the British, he did not give them any ships or maps, or even geographical attack advice. He certainly didn’t stay neutral. His sentiments, as clearly stated in his letters in the archives, were wholly with the United States, his adoptive country, as proven by his actions.

In the end, the Laffites never got their ships back for free, or most of the goods that were taken in the raid. Ross had beaten Jean to the punch about approaching Washington authorities regarding proceeds from sales of the raid items, and he successfully lobbied for a congressional bill to approve the award to Patterson, Ross and their soldiers. That was not approved until 1817, by which time Ross had died, so Patterson was the one who benefitted from the $50,000 windfall.

Madison had promised the Baratarians a full pardon for anyone who fought for the US in the New Orleans campaign, but neither Laffite ever applied through the governor for one of these pardons. Medals, swords, and all sorts of praise were heaped on Gen. Jackson after Jan. 8, 1815, but the Laffites only got a few appreciative words from the general in newspaper articles.

Chalmette Battlefield is now a part of Jean Lafitte National Historical Park, and it will celebrate the 200th anniversary of that glorious victory day on Jan. 8, 1815. Let’s hope the ceremonies include some recognition of Jean Laffite, Pierre Laffite. and the Baratarians. It would be the proper and fitting thing to do.

Recent Comments