The Courtship of Theodosia Bartow Prevost and Aaron Burr

June 8, 2013 in American History, general history

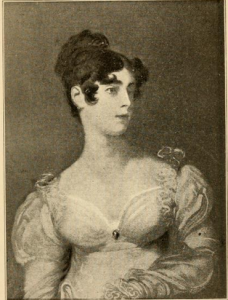

The Hermitage Credit:thehermitage.org

She was the posthumous only child of Theodosius Bartow and Anne Stillwell Bartow. Named after her father, she bequeathed her given name, which she got from a father she never met, to a daughter that she left an orphan at the age of eleven. Known for her intelligence, wit and good character, Theodosia Bartow Burr was not said to be particularly beautiful. But she was deeply loved and chosen by Aaron Burr as his bride, despite being ten years his senior and already afflicted with cancer.

The facts prior to Theodosia Bartow Prevost’s association with Aaron Burr are known only in their starkness. Following the death of her father, Theodosius Bartow, in a carriage accident, her mother Anne Stillwell married Philip De Visme and had several children by him, half-siblings of Theodosia. Theodosia grew up in an educated, intellectually stimulating household and she spoke and read French as well as English. She married Jacques Marcus Prevost and bore him five children. He was in the British army, but of French Swiss descent. The couple established themselves in Bergen County, New Jersey, in an estate called The Hermitage. Eventually, after leading several campaigns against the American revolutionaries, Jacques Prevost was serving as governor of Georgia in 1778 under the British and then was later stationed in Jamaica in 1780, but his wife Theodosia remained behind in New Jersey at the Hermitage.

It is at about this time that Aaron Burr, serving the Continental Army, came on the scene.They met in August of 1778 on a trip down the Hudson. It happened like this: General Alexander sent Burr on a spy mission after his heat stoke following the Battle of Monmouth. He was to check on British positions in preparation for a combined attack by the continental army and French regiments. At the time, the French had a fleet off Sandy Hook. Burr was ordered to West Point in July of 1778. General Washington then ordered him to escort three highly placed Loyalists under a white flag down the Hudson River to the enemy side. Theodosia Prevost, wanting to rejoin family in New York City, got permission from General Alexander to board the same ship, along with her half-sister, Caty De Visme and a servant. Burr was the one who added their names to the passenger list. The trip took five days, and that was enough time to change everything.

After that, Burr visited Theodosia Prevost and her family in the Hermitage quite frequently and even wrote to his sister Sally about her, saying she had “an honest and affectionate heart.”

After his resignation from the Army in 1779, Burr was a frequent visitor at the Hermitage. Everybody who knew them knew that they were in love. Burr’s cousin Thaddeus wrote to him: ““I won’t joke you any more about a certain lady.” In 1780, Major Prevost, Theodosia’s husband, who was serving under the British in Jamaica, was gravely injured. He sent home reports that the medical conditions there were poor, and anticipating his own death, he sent his teenaged sons who were with him back to their mother in America.

Theodosia Bartow Prevost Burr’s letters to other members of her family do not seem to have been preserved. But her letters to Aaron Burr show a remarkable ability to discuss philosophical issues as well as matters of the heart. She believed in the methods of education and the morality set forth by Rousseau in La Nouvelle Heloise, and was very much opposed to the advice of Lord Chesterfield to his son, even though Aaron Burr thought it good.

Your opinion of Voltaire pleases me, as it proves your judgment above being biased by the prejudices of others. The English, from national jealousy and enmity to the French, detract him. Divines, with more justice, as he exposes himself to their censure. It is even their duty to contemn his tenets; but, without being his disciple, we may do justice to his merit, and admire him as a judicious, ingenious author.

I will not say the same of your system of education. Rousseau has completed his work. The indulgence you applaud in Chesterfield is the only part of his writings I think reprehensible. Such lessons from so able a pen are dangerous to a young mind, and ought never to be read till the judgment and heart are established in virtue. If Rousseau’s ghost can reach this quarter of the globe, he will certainly haunt you for this scheme–’tis striking at the root of his design, and destroying the main purport of his admirable production. Les foiblesses de l’humanite, is an easy apology; or rather, a license to practise intemperance; and is particularly agreeable and flattering to such practitioners, as it brings the most virtuous on a level with the vicious. But I am fully of opinion that it is a much greater chimera than the world are willing to acknowledge. Virtue, like religion, degenerates to nothing, because it is convenient to neglect her precepts. You have, undoubtedly, a mind superior to the contagion.

When all the world turn envoys, Chesterfield will be their proper guide. Morality and virtue are not necessary qualifications–those only are to be attended to that tend to the public weal. But when parents have no ambitious views, or rather, when they are of the more exalted kind, when they wish to form a happy, respectable member of society–a firm, pleasing support to their declining life, Emilius shall be the model. A man so formed must be approved by his Creator, and more useful to mankind than ten thousand modern beaux.

Later biographers used this particular letter to explore the contrasting attitudes held by Aaron Burr and Theodosia Bartow Prevost Burr toward the subject of educating their daughter, but it is important to remember that at the time this letter was written ( February 12, 1781), they had no children in common. Theodosia was a married woman, and Aaron Burr was her suitor. And the topic of this letter was whether committing adultery is all right. Theodosia, using literary allusions to Jean-JacquesRousseau and Lord Chesterfield, was letting Aaron Burr know that she thought it was not all right. Although her husband had already died, Theodosia did not know this, and she was adamant in her insistence that self-restraint was a better course of action than giving in to passions

There was already much gossip about the couple, even though they had not in fact acted on their love and carried on their courtship mainly through correspondence. In May of 1781 Theodosia wrote to Aaron:

Our being the subject of much inquiry, conjecture, and calumny, is no more than we ought to expect. My attention to you was ever pointed enough to attract the observation of those who visited the house. Your esteem more than compensated for the worst they could say. When I am sensible I can make you and myself happy, I will readily join you to suppress their malice. But, till I am confident of this, I cannot think of our union. Till then I shall take shelter under the roof of my dear mother, where, by joining stock, we shall have sufficient to stem the torrent of adversity.

It was not until December 30, 1781 that Caty De Visme wrote to Burr from The Hermitage: “If you have not seen the York Gazette, the following account will be news to you; We hear from Jamaica that Lieutenant Col. Prevost, Major of the 60th foot, died at that place in October last.’”

They were now free to marry. But the mores of society required a suitable period of mourning. For a widow to marry after less than a year of learning of her husband’s death was scandalous. And yet they had waited so long already.

On July 2, 1782 at the wedding of Cathy De Visme to Joseph Browne, Aaron Burr, Esq., of the State of New York, was married to Theodosia Prevost, widow, of the State of New Jersey. The marriage certificate, however, is dated July 6, 1782. In any event, their daughter Theodosia was not born until June 21, 1783, proving that they had waited patiently. They married when they did not because they had to, but because they wanted to wait no more. The marriage was to last twelve years, until Theodosia Bartow Prevost Burr’s death on May 18, 1794. Aaron Burr never got over her.

References

The Letters of Theodosia Prevost Burr from FamilTales.org

http://www.thehermitage.org/history/history_people_prevost_theodosia.html

http://www.authorama.com/famous-affinities-of-history-ii-3.html

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=63069344

Recent Comments