Capt. Percy’s Folly at Fort Bowyer

September 14, 2014 in American History, general history, History, Louisiana History, Native American History

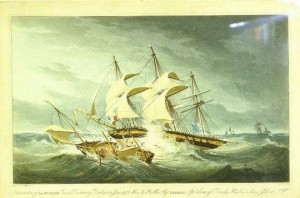

This shows the first battle of Fort Bowyer, with positions of the ships. The Anaconda shown is not correct: this ship was the Childers.

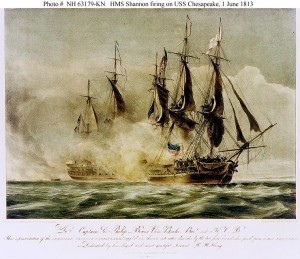

Young British Capt. William H. Percy found himself in dire straits on the afternoon of Sept. 15, 1814. His ship, the sixth rate class HMS Hermes, was mired for the second time that day on a sand bar in shoal water within 150 yards of Fort Bowyer near Mobile Bay, and the Americans at the fort were taking full advantage of the ship’s predicament, mercilessly strafing it with grape shot, langrege and musket fire.

To Percy’s horror, plans for an easy British attack on the fort had gone terribly awry, thanks to almost no wind, a shot to the anchor line, shallower water than expected, and the fact that the American fort’s 130 defenders led by Major William Lawrence were much better entrenched and armed than earlier British spying missions had forecast.

More than a third of Percy’s men were casualties of the devastating raking ammo, which ripped sails into rags, and strafed all the rigging of the Hermes. There was only one way out to avoid more loss of British lives: Capt. Percy had to disembark everyone, then personally set fire to his own ship, which blew up a few hours later as the flames hit the powder magazine. Perhaps due to the thick barrage, no attempt seems to have been made to spike any of the Hermes’ 22 guns; a few of the cannons were salvaged later by Lawrence and his men.

The rest of the four-ship British squadron couldn’t save the Hermes as, with the exception of the HMS Sophie under Capt. Nicholas Lockyer, a contrary wind and strong tide prevented them from getting close enough to effectively fire back at the fort. The Sophie, like the flagship Hermes, suffered damage while firing some broadsides at the fort, but the Sophie managed to tack away out of range of the worst of it. The captains and crews of HMS Carron and HMS Childers, and the land forces of the Royal Colonial Marines and some 600 Indians on Mobile Point could only watch in dismay as the Hermes was battered. An earlier foray from the land side by the Marines and Indians, armed with a Howitzer, had seen but little success on the fort’s flank due to the Americans’ secured entrenchment even on the weak side.

British plans for a great victory which would lead them to an easy route to Baton Rouge and control of the Mississippi River had literally blown up in their faces.

As a result of his actions, Percy faced a tense court-martial Jan. 18, 1815, onboard the HMS Cydnus off Cat Island. Presiding was Edward Codrington, rear admiral of the White, captain of the Fleet, and third officer in command of His Majesty’s ships and vessels in the Gulf of Mexico. Percy was exonerated for destroying his own ship at a critical time in the Gulf Coast campaign, but he would never again be entrusted as captain of any ship. He had torched his own naval career at the same time that he torched his ship.

The primary evidence at the court-martial was Percy’s Sept. 16, 1814 letter to Vice Admiral A. Cochrane, a lengthy and detailed account of what happened during the whole action to try to seize control of Fort Bowyer.

“Having embarked Brevet Lieut. Col. Nicolls and his detachment of Marines and Indians…, on the 11th instant I left this Port (Pensacola) in company with His Majesty’s Ships Carron and Childers and off the entrance of it fell in with and took with me His Majesty’s Sloop Sophie, Capt. Lockyer, returning from Barataria…acquainting me with the ill success of his mission (to enlist Laffite and the use of his light draft schooners in the attack on Mobile).

On the evening of the 12th I landed Lieut. Col. Nicolls with his party about 9 miles to the Eastward of Fort Bowyer and proceeded .. off the Bar of Mobile, which we were prevented from passing by contrary winds until the afternoon of the 15th, during which time the Enemy had an opportunity of strengthening themselves, which we perceived them doing; having reconnoitred in the Boats within half a mile of the Battery. I had previously communicated to the Captains of the Squadron the plan of attack, and at 2:30 p.m. on the abovementioned day having a light breeze from the Westward I made the Signal for the Squadron to weigh, and at 3:10 passed the Bar in the following line of Battle: Hermes, Sophie, Carron & Childers.

At 4:16 the Fort commenced firing, which was not returned until 4:30 when being within Pistol shot of it, I opened my broadside, and anchored by the Head and Stern, at 4:40 the Sophie having gained her station did the same; at this time the wind, having died away and a strong ebb tide having made, notwithstanding their exertions, Captains Spencer (Carron) and Umfreville (Childers) finding their ships losing ground, and that they could not possibly be brought into their appointed stations, anchored, but too far off to be of any great assistance to the Hermes or Sophie, against whom the great body of the fire was directed. At 5:30 the bow spring (cable) being shot away, the Hermes swung with Head to the Fort and grounded, whence she laid exposed to a severe raking fire, unable to return except with one carronade and the small arms in the Tops; at 5:40 finding the Ship floated forward, I ordered the small bower cable to be cut, and the Spanker to be set, there being a light wind to assist, with the intention of bringing the Larboard Broadside to bear, and having succeeded in that, I let go the Best bower anchor to steady the ship forward and recommenced the Action.

At 6:10 finding that we made no visible impression on the Fort, and having lost a considerable number of our Men and being able only occasionally to fire a few guns on the larboard side in consequence of the little effect the light wind had on the ship, I cut the cables and springs and attempted to drop clear of the fort with the strong tide then running, every sail having been rendered perfectly unserviceable and all the rigging being shot away, in doing which, unfortunately His Majesty’s ship again grounded with her Stern to the Fort.

There being now no possibility of returning an effective fire from the ship I made the Signal No. 203, it having been already arranged that the storming parties destined to have acted in conjunction with the forces landed under Lieut. Col. Nicolls were to assemble on board the Sophie to put themselves under the orders of Captain Lockyer. While they were assembling Captains Lockyer and Spencer came on board the Hermes, and on my desiring their opinion as to the probable result of an attempt to escalade the fort, they both agreed that it was impracticable under existing circumstances (at the same time offering their services to lead the party if it should be sent) In this opinion I (concurred) with them.

The Ship being entirely disabled and there being no possibility to move her from the position in which she lay exposed I thought it unjustifiable to expose the remaining men to the showers of grape and langrege incessantly poured in, and Captains Lockyer and Spencer who saw the state of the ship at the same time giving it as their decided opinions that she could not by any means be got off, I determined to destroy her and ordered Captain Lockyer to return to the Sophie and send the boats remaining in the squadron to remove the wounded and the rest of the crew and to weigh; at the same time I made the signal for the squadron to prepare to do so. The crew being removed and seeing the rest of the squadron under weigh, at 7:20 assisted by M.A. Matthews 2nd Lieutenant (Mr. Maingy, 1st Lieut having been ordered away to take charge of the people) I performed the painful duty of setting fire to His Majestys Ship.

I then went on board the Sophie and finding it impossible to cross the bar in the night, I anchored the ships about 1 ½ mile from the Fort, and at 10 I had the melancholy satisfaction of seeing His Majestys ship blow up in the same place in which I left her.

The squadron having during the night partly repaired the damages in their rigging, at daylight I took them out of the bar having previously communicated with the Commanding Officer of the detachment on shore, and desired that he would fall back upon bon secour.

Altho this attack has unfortunately failed, I should be guilty of the greatest injustice did I not acquaint you sir of the high sense I entertain of the intrepidity and coolness displayed throughout this action by the officers, petty officers and crew of His Majestys late ship Hermes, from Mr. Peter Maingy the 1st Lieut. I received the greatest assistance, and I beg to mention the activity and good conduct of M. Alfred Mathews 2nd Lieut.; in Mr. Pyne the late Master (who fell early in the action) the service has sustained a severe loss.

Lieut. Col. Nicolls having been seriously ill on shore had been removed to the Hermes and was on board during the Action; it is almost unnecessary for me to mention of him that he was actively assisting on deck, to which post he returned, after a severe wound which he had received in the Head had been dressed.

W.H. Percy, Captain”

Nicolls had been especially unlucky that day. He had been charged with leading his Royal Colonial Marines and the Indians on a land attack toward the rear of the fort, but a severe attack of dysentery sent him early to the Hermes for treatment from the ship’s surgeon, and while he was watching the action from its deck, a stray splinter from a fire of grapeshot hit him in the head and cost him the sight in one eye.

The “butcher’s bill” of the British side was 232, with 162 of that number killed: the Americans, by contrast, had only eight casualties, with four killed. The Hermes’ surgeon’s report reflects the gruesome nature of the wounds: Edward Hall, 34, landsman, left hand torn off by a cannon ball; William James, 16, struck on left knee with a cannon ball, leg amputated on HMS Carron; Walter Price, wounded in the head by grapeshot while serving on the HMS Sophie, died 15 days later. Many of the wounded survived amputations only to die a few days later from tetanus, according to the surgeon’s notes.

Born in 1788, Percy was the sixth son of Algernon Percy, the first Earl of Beverley, and started his naval career in 1801. He was promoted to commander in 1810, with his first ship being the HMS Mermaid in 1811. At that time, he transported troops beween Britain and Iberia during the Peninsular War. He was made post captain on March 21, 1812. His last (and only second) command was the HMS Hermes, which he assumed in April, 1814. After that ship’s destruction, Percy carried back to Britain the dispatches announcing the British defeat at the Battle of New Orleans. From 1818-1826, Percy was active in politics as the Tory MP for Stamford, Lincolnshire. Later, he was made a rear admiral on the retired list in 1846.

Historian Arsene Lacarriere Latour, writing in 1815, summed up Percy’s misadventure best with this eloquent assessment:

“Instead of the laurels he was so confident of gathering, he carried off the shame of having been repulsed by a handful of men, inferior by nine-tenths to the forces he commanded. Instead of possessing himself of an important point, very advantageous for the military operations contemplated by his government, he left under the guns of fort Bowyer the wrecks of his own vessel, and the dead bodies of one hundred and sixty-two of his men. Instead of returning to Pensacola in triumph, offering the Spaniards, as a reward for their good wishes and assistance, a portion of the laurels obtained, and the pleasure of seeing the American prisoners he was confident of taking, he brought back to that port, which had witnessed his extravagant boasting, nothing but three shattered vessels full of wounded men.”

For further reading:

Latour, Arsene Lacarriere. Historical Memoir of the War in West Florida and Louisiana in 1814-15, with an Atlas, Expanded Edition, edited by Gene A. Smith, The Historic New Orleans Collection and University of Florida, 1999.

Recent Comments