-

Pam Keyes is the Research Coordinator of the Laffite Society and a well known expert on the history of Jean Laffite and of the artifacts and written evidence that are available on the life of the famous privateer. In this interview, I asked her questions concerning Jean Laffite that have been preoccupying me for some time.

Pam discusses her own history with the Laffite Society and its precursors, the primary documents that she has examined herself that pertain to Jean Laffite, the evolution of Jean Laffite’s signature, the controversial Journal of Jean Laffite, and the way Jean Laffite may have viewed himself.

- Could you tell us a little of how you came to know about Jean Laffite and to take an interest in his life story?

I first came across Jean Laffite when I was nine years old and my parents and I went to a double feature movie in 1964 at the drive-in featuring the 1958 “The Buccaneer” along with Danny Kaye’s movie “The Five Pennies.” I was quite enthralled by the movie (not to mention the extreme charisma of Yul Brynner who played Jean Laffite) and the message of how Laffite helped the Americans even after they blew Barataria to bits. There was even a Classics Illustrated comic book about the movie which I got at the neighborhood grocery store that week, and well, everything just sort of snowballed from there. Of course I found out from the encyclopedia that the movie had been romanticized by DeMille, and there was no governor’s daughter, nor Corinthian pirated American ship, etc., but the basic story was true.

My local library had a couple of books about the Battle of New Orleans in the children’s section, but nothing else. When I got a bit older, around 11 or 12, I found Madelyn Fabiola Kent’s novel “The Corsair” in the adult section, and read it voraciously. I did not know at the time that Ms. Kent had used one of the Jean Laffite journals for background information for her novel. Puberty hit, and my interest in Laffite dropped off by the wayside until I was around 15, when I started looking for more about Laffite. This was not easy to do, considering I lived in Oklahoma, some 750 miles from New Orleans, and at the time there was no such thing as the internet, only letters.

In Antique Trader’s newspaper which the library carried, I found a classified ad listing a copy of Stanley Arthur’s “Jean Laffite, Gentleman Rover,” and purchased it. I remember it was quite exciting to learn from that book that there were Laffite manuscripts and journals around, and that a descendant was living in Kansas City in the 1950s when the book was published. I wanted to see the frontispiece 1804 portrait of Laffite in person, and I was sure that the museum at Kansas City probably had it, so I convinced my parents to take me to Kansas City on a search. No portrait was found, nor any other leads on that trip, and I returned dejected, but not ready to give up.

I placed an ad in the Kansas City Star newspaper asking for information about the Laffite portrait from anyone who knew anything about it. One of John A. Lafitte’s old neighbors in Kansas City responded and gave me the name and address of the descendant’s ex-wife, Lacie Surratt, who had remarried and moved to Spartanburg, S.C. Lacie gave me the name of her friend Audrey Lloyd, a Laffite researcher in Midland, Texas, and Audrey in turn pointed me to Robert Vogel, who was just at that time starting a new group called The Laffite Study Group, based in Cottage Grove, Minnesota. Vogel led me to longtime Laffite researchers Ray and Sue Thompson at Gulfport, Miss., Dr. Jane de Grummond, a history professor at Louisiana State University, John Howells, a Laffite enthusiast at Houston, Texas, and historian Dr. Jack D.L. Holmes.

We all carried on a lengthy correspondence over the years. Vogel came to visit me in Oklahoma when he was on his way down south one year, and I visited Dr. de Grummond at her home in Baton Rouge three times, but most of us never met face to face. I had corresponded with Howells for 25 years before I met him at Galveston in the late 1990s when I went to a meeting of the Laffite Society, a group which had formed after the Laffite Study Group disbanded around 1991. I also met Lionel Bienvenue, who served as historian at Chalmette Battlefield, around the time the Jean Lafitte National Historical Park was being created. I was a member of the citizen input group for plans for the park in the 1980s.

There’s a lot, lot more I could relate, but that’s the gist of how my interest in Laffite started. My favorite movie to this day is the 1958 Buccaneer.

- What primary documents have you examined over the years concerning Jean Laffite’s life? The signature of Jean Laffite in his letter to President Madison is quite different from the signature in the Journal of Jean Laffite. Is this dispositive of the issue of authenticity of the journal? Do you think the same man could have made both signatures? How does each of the signatures compare to other signatures attributed to Jean Laffite in other documents?

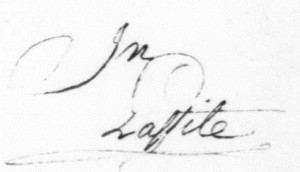

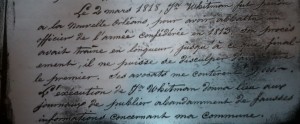

The signature of the letter to President Madison

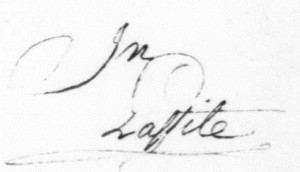

The very first primary document signed by Jean Laffite that I ever saw was his 1815 letter to President Madison. I was 11 years old at the time, walking through a manuscript display at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., when I spotted the Laffite letter. Somehow, I intuitively knew even then that Jean had not written the body of the letter, with the incorrect spellings, etc. Some years later, after seeing other Laffite manuscripts, this early assumption on my part turned out to be valid. The signature, however, is correct for Jean at that period of his life. Both Jean and Pierre Laffite’s signatures changed over the years: Pierre’s, due to ill health; Jean’s, due to a psychological shift, based upon my study of the few available manuscripts available. There are several notarial documents in the New Orleans Notarial Archives signed by Pierre, but only a few that are signed by Jean, and all bear a rather small understated form of his pre-Battle of New Orleans signature, usually with the first name being shortened to Jn with a strike through the first name from the cross on the double t’s, and the surname enclosed in a circle paraph.

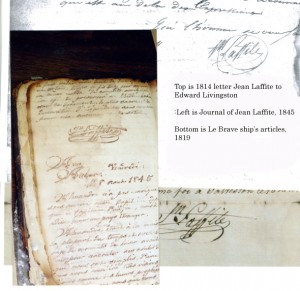

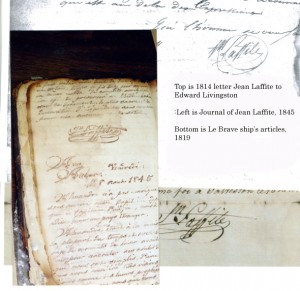

In the New Orleans city archives at the New Orleans library, I happened across a previously unknown Jean Laffite signed document when I opened up a case file pertaining to Vincent Gambie from 1815, and a statement signed by Jean Laffite quite literally dropped into my lap. This one bore a transitional signature, still small, but without the strike-through. Some Laffite manuscripts I have only seen in exact copies and color photographs, such as the Oct. 4, 1814 French letter Jean Laffite wrote to Edward Livingston at a very tumultuous time in Jean’s life. This one has the first name struck through, and the last name circled to focus importance on the Laffite surname.

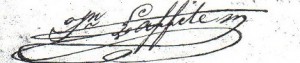

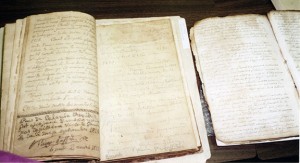

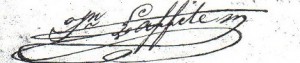

Next up for examination is the Laffite signature on the Le Brave ship’s articles document, from August 18, 1819 (the original is at the federal archive at Fort Worth, ironically the closest authentic Laffite manuscript to me, but I have never been there in person. I do, however, have an exact photographic image of the complete manuscript). The Le Brave signature is bold, larger than any of the preceding signatures, but with the same slant and same general form, with some significant differences: the strike through on the first name has now become an underline, and the first and last names are one unit. No longer is the Laffite name by itself encircled, but underlined with a fancy paraph that ties the bottom of the two f’s together. The ink pressure is heavy and fluid, with no hesitation. The whole body of the Le Brave document appears to be in the same penmanship as the signature, and that is interesting, too, as every millimeter of the paper is used on the right margin, sometimes with a curious dash where no dash is really needed. The handwriting is very legible. The next sample, also a photograph, is an 1819 letter to James Long which Jean Laffite wrote and signed (this is in the Mirabeau Lamar collection at the Texas State Archives, Austin.) The handwriting and penmanship are virtually identical to the Le Brave document.

The real test of a Jean Laffite signature and penmanship awaited me in examining first hand the Laffite Journal collection at Sam Houston Library, Liberty, Texas. I had the exact size color images of the Le Brave document of 1819 with me to compare side by side with the Laffite Journal signatures and handwriting. The Laffite Journal itself was a match, but some of the accompanying manuscript was not. Based on this comparison, it is my (admittedly layman) opinion that the Laffite Journal is authentic and not a forgery. No inconsistencies with the handwriting were found within the entire Laffite Journal. As for the language of the Journal, which at first glance appears to be an archaic Creole French, linguist Gene Marshall said it is polyglot with mixtures of English, Spanish and French, and shows a good command of grammar for the time

Jean Laffite signature from the Journal

- The letter to President Madison contains a number of spelling errors as well as a poor choice of vocabulary. He spelled sentiment with an initial letter “c”, even though it is a French word borrowed into English and spelled in English the same as in French. He used the word “notorious” to describe himself and his associates without realizing that it had a bad connotation. What do his spelling errors and diction choices tell us about Jean Laffite’s command of English, his command of other languages, such as French and Spanish, his education and his social class?

Although Jean Laffite appears to not have been able to write fluently in English, he could read it fluently, as evidenced by his apparent favorite news publication, the Jeffersonian political editorial newspaper Aurora of Philadelphia, Penn. The fact that he was highly literate in a language not his own demonstrates that either he had had advanced schooling, or was intelligent enough to teach himself. According to historical accounts by contemporaries, Jean seems to have been better at conversational English than the written form, so perhaps he did teach himself by being around English speakers. This ability to do business in three languages plus a knowledge of proper manners helped secure his social status, too, as a middle man bridge between the rough, mostly illiterate ship captains, and the old French and Spanish families of New Orleans and environs.

- How many copies of The Journal of Jean Laffite were there when John Andrechyne Laflin first made it public? Were they each believed to be in the hand of Jean Laffite? Is it possible that the original document could have been copied by hand by someone else so that each Laffite heir could have a copy?

We only know about two copies of the Laffite Journal: the one that Madelyn Kent read for her background material in The Corsair, and which she obtained from John A. Lafitte, who borrowed it from a cousin (so he said), and the Laffite Journal which is in the collection at Sam Houston. No copies of the one read by Kent are known to exist, but it is known that John A. did have to sue her in order to get it back. The cousin who owned it has never been found. The Laffite Journal we do have copies of is definitely a copy of an original document, but it is a copy made by the same person as who wrote the first, that is, it is completely in the Jean Laffite handwriting of the authentic Le Brave document of 1819. There are no mistakes crossed out, and the writing goes into the right hand edge, even into the gutter of the journal book. I used to own a similar autobiographical journal, an ms written by a Connecticut shipbuilder in 1848 for his descendants, and it also was a handwritten copy, one of five written for his grandchildren. There were no writing mistakes in it, either. Stylistically it was very similar to the Laffite Journal, leading me to believe in the 1840s, that was the thing some men did, was write out the stories of their lives for their descendants. The thing that is striking about the Laffite Journal is he starts right off saying he doesn’t want his descendants to release the contents of the journal until 1952 (one hundred and seven years from the start of the journal). John A. Lafitte could not read French, so he couldn’t read that, but interestingly, 1952 is precisely when the contents of the journal did begin to be released.

- In the case of those who are firm in their belief that the Journal of Jean Laffite is a forgery, what evidence do they base this conclusion on? Has the the Journal been discredited to the satisfaction of all reputable historians or is this still an open question in historical circles?

There are many reasons why so many people consider the Laffite Journal a forgery, but the main one is the fact that the person who is first known to have had it, John A. Lafitte, was a proven con man whose abused wife secretly told her friend Audrey Lloyd that “he made it all up” and studied how to age paper and ink, etc., etc.

This pretty much damned John A. Lafitte and the Journal collection in historical circles, but only long after he had died. There are signs in the Laffite collection at Sam Houston that some things were obviously added and altered to enhance the value of the collection, and the whole collection went though two fires, one at John’s A’s house, and one at a tv station. He tried to sell the collection to autograph dealer Charles Hamilton at first, and Hamilton was quite enthusiastic about it, but then fishtailed out. The collection was sold shortly before John A’s death for $15,000 to Texas autograph dealer William Simpson, and Simpson had his friend, John Howells, examine it in detail for a couple of years before selling it to former Texas governor Price Daniel. (Howells had the collection sitting underneath his coffee table for those two years while he tried to authenticate it with examinations of the handwriting and paper). When the Laffite Journal first became public, historians Jane de Grummond and Harris Gaylord Warren both thought it was authentic back in the 1950s and 1960s. Dr. de Grummond believed in its authenticity until she died. I don’t know if Warren changed his mind, I didn’t correspond with him. Robert Vogel is extremely anti-Laffite Journal, a position he shared with Ray and Sue Thompson.

Because there was so much doubt about the circumstances surrounding the Laffite Journal’s provenance, most serious historians of later years haven’t even bothered to examine it in detail themselves. The only one who has done so is William C. Davis, who spent three days looking at it. He based his unbiased conclusion that it wasn’t authentic on the surrounding material in the collection, plus historical inaccuracies in the translated journal. He is not a handwriting expert, so did not make a comparison in that respect. He weighed it solely based on its historical aspects, and noted that there is nothing in it that wasn’t in some book or newspaper article published before the Laffite Journal came to light. One current historian who does think it is authentic is Winston Groom, but he never conducted an onsite examination of the Laffite Journal and collection, confining his research to telephone questions of the Sam Houston archivist at the time, Robert Schaadt (who also believes in the authenticity of the Laffite Journal).

The final chapter remains to be written about the Laffite Journal, though; it has never successfully been proven to be a forgery, nor has it ever been proven to be authentic. It remains in a gray, enigmatic haze. With modern technology, the question of its authenticity could be determined forensically, but no one wishes to do this. Sometimes people prefer to let things stay a mystery even when an answer can be obtained.

- Is there any documentary evidence, such as birth certificates, marriage certificates, passports or other official documents to verify the lineage of the descendants of Jean Laffite?

Re documentary evidence of descendants of Jean Laffite, there is only a bit regarding the birth and death of his son by his black mistress, Catherine Villard. There are some indications that he had a daughter, Adele, by Catherine. Adele’s descendants seem to mostly be in Puerto Rico now. The black descendants of both Pierre and Jean Laffite are hard to track because during the 1800s, most passed for white and intermarried with whites by hiding any traces of their black lineage. This is especially true of Cubans who migrated to Puerto Rico. Several direct descendants of Pierre Laffite and his black mistress Marie Villard have been located, and there is every reason to believe that Jean could have just as many. Regarding the white wives and marriages for Jean given in the Laffite Journal, no documentary evidence has been found. Likewise, no evidence has been found for Jean’s white children, except for one statement from the Sallier family of Lake Charles that a daughter of their family was named for Denise Laffite.

7. What can we learn about the character of Jean Laffite from the various letters to the editor that he was known to have sent in during his lifetime? What were his politics? How did he see himself as a public figure?

Jean Laffite did not leave many letters from which to interpret how he felt about things, or even what his personality was like, but the one prominent letter to the editor which he did write gives some clues about who he was, and his self-image. This letter, published in the Aurora newspaper of Oct. 3, 1815, was written while Jean was staying in Baltimore before proceeding to Washington, D.C., to try to get an audience with President Madison. The weekly Aurora publication of Philadelphia was the pre-eminent Jeffersonian publication of its time nationally. Jean’s choice of this newspaper to publish his letter shows that he shared its pro Jeffersonian democracy and anti-Federalist sentiments. It is not surprising that he would like this editorial stance, given that the paper was heavily sympathetic to the French and Napoleon.

In the letter Jean takes issue with lies that have been published in various gazettes the past two years calling him a pirate who preyed on American ships, and says he has letters of marque which prove that he and those working for him were privateers. and he never committed an act of piracy. He further states that if anyone can show that he or those he ordered did commit an act of piracy or injustice, they should contact the appropriate officials and he would willingly appear to answer any such charges. He did not want people to call him a pirate, because in those days, pirates were hung. Privateers, who were licensed by their letters of marque from Cartagena or Buenos Ayres to take Spanish ships, were respectable captains who made fortunes legally from their captured prizes. Pirates were regarded as ruffian murderers who thought nothing of torturing captured crews in truly horrible ways. Privateers were thought of as captains who treated their captured prizes humanely. Pirates were regarded as scum. Privateers were honorable, and often gentlemen. However, the only true difference between the two often just boiled down to a piece of paper with a seal attached, a paper which might or might not be legitimately from Cartagena or Buenos Ayres.

What can be learned about Jean from that letter to the editor? He wanted to be regarded as a proper gentleman privateer captain, someone who could be respected. He cared about his social standing, not just in the New Orleans area, but at large, which is why he wrote the letter to the editor.

This desire for respectability is quite likely the reason why the Laffites assisted Jackson and the Americans during the British invasion of Louisiana. Jean and his brother Pierre were already socially accepted by the French residents of New Orleans as middlemen for smuggling ventures, but they seem to have both wanted acceptance by the Americans and fractious Gov. William C.C. Claiborne as well. Jackson’s lack of flints, powder, and skilled artillerymen provided the perfect opportunity to gain respect, especially after the Americans destroyed the Laffite base at Grande Terre a few months before and jailed several Baratarians captured there, and after Pierre had spent a miserable summer in the Cabildo jail before escaping. The Laffites could have packed up and left for other places, but they stayed put to help, because that’s what they both wanted to do. Why? It seems quite obvious they wanted to be thought honorable, even in the face of extreme adversity from those they would help. A presidential pardon had been extended to them, but neither Laffite ever accepted one.

Jean Laffite gained prominence over his brother Pierre in the aftermath of the Battle of New Orleans, but something happened that soured him on New Orleans and made him want to not rest on his laurels. Jean did not become a hero overnight. New Orleans politics were as corrupt then as they are now, and the Laffites found themselves fighting to get restitution for the losses they had suffered from the Baratarian raid. Most of it went into the pockets of raiders Patterson and Ross. Jean made his trip to the East Coast in late 1815 to try to get restitution from the president, but the mission was a failure. He must have been very depressed upon his return, enough so a mapping expedition into Arkansas territory with his friend Arsene Latour seemed like a good idea to get away from it all. He accepted a new role along with Pierre as a spy for Spain, even though they had preyed on Spanish ships. Jean made a coup on Louis Aury and assumed control of Galveston, a place where he finally realized his potential without the domineering brother Pierre nearby.

This happy state of affairs wouldn’t last long, though, as the severe hurricane of Sept. 12, 1818, made a direct hit on Galveston and nearly decimated the Laffite camp. Jean was strong enough emotionally to take charge of the recovery efforts and was able to get food and water to the other survivors, but things were never as good after that. The year of 1819 was a year of financial ruin for the United States, and it was likewise a horrible year for Jean Laffite, as his newly purchased ship Le Brave, with his signed and fully written ship’s articles onboard, was caught in an act of piracy off the Belize by US authorities. The captain and crew, with two exceptions, were found guilty of piracy in New Orleans and sentenced to be hung. Jean Laffite had reached his nadir, his name was attached to a pirate ship. Under US pressure and protection, he abandoned Galveston not long before the Le Brave pirates were strung from the yardarms at New Orleans.

Jean and Pierre drifted toward Las Mujeres, then split apart. Jean got caught by Cuban authorities but due to some friends there got put in the hospital and managed to escape, then made it to Cartagena to get a commission as a privateer on the General Santander. He was a licensed privateer again, but not for very long, as he ran afoul of merchants in Kingston who petitioned for his arrest due to piracy on merchant vessels in the Bay of Honduras and Balize. A newspaper account in the Gaceta de Colombia claimed he had died in a sea battle with two Spanish vessels off the Honduran coast, but it seems like too neat and tidy an ending. He needed to disappear, considering there was a noose waiting for him in Kingston. Newspaper stories were easy to make up. So did he give up the sea life and return to the US under an assumed name, as the Laffite Journal indicates? Well, since the handwriting and signature of the Laffite Journal of the 1840s is identical to that of the Le Brave ship’s articles of 1819, the answer must be yes.

RELATED ARTICLES

http://www.historiaobscura.com/the-scrapbook-of-jean-laffite/

http://www.pubwages.com/26/lobbying-the-madisons-letters-to-james-and-dolley

http://www.historiaobscura.com/the-new-orleans-bank-run-of-1814/

://www.bubblews.com/news/1203349-the-signature-of-jean-laffite

Recent Comments