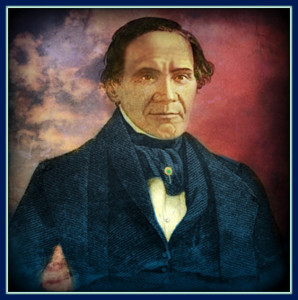

Auguste Davezac, the Creole Celebrity That History Forgot

October 2, 2018 in American History, Caribbean History, general history, History, Legal History, Louisiana History

A noise began from the back of the massive crowd, light at first, then swelling gradually as it spread, as the next speaker was introduced to the throng of some 6,000 present. The name of Major Davezac was repeated, ever more loudly, by a thousand voices, as an older gentleman removed his top hat and ascended to an outdoor platform lit by torches and colored lamps in Baltimore.

In addition to banners, the platform featured a large arch covered in hickory boughs interlaced with purple pokeberries and multi-colored dahlias. Some 1,500 ladies, all occupying the front seats, waved their white handkerchiefs and floral bouquets, a tribute paid to the old French Creole veteran who gazed out over the crowd and smiled as cheers for him began before he ever spoke__it was Sept. 21, 1844, and Major Auguste Davezac, the right hand man of Gen. Andrew Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans 29 years earlier, was ready to deliver one of his dynamic Democratic speeches for the Polk-Dallas presidential ticket.

The opposing Whig party, like the British at Chalmette, didn’t stand a chance. Democrat James K. Polk won the Presidency in that November’s election.

A witness that night wrote from Baltimore that Davezac’s delivery was rapid, but distinct, and his voice strong, adding “What makes him specially among the popular speakers is the power he exercises at once over the sympathies of his audience. To use his own phrase, ‘there is a continued stream of galvanic fluid, flowing from the people to him, and returning, in sounds from his lips, to their hearts.’ He loves democracy as a young lover the maid of his first affections. His faith in its institution, in its power to throw down all obstacles in the way of its fated march, is like that of an apostle in his creed. He has read much, yet never cites. When he describes natural sceneries, you feel that he sees with the eyes of a painter; when he expatiates on heroic deeds, one fancies the poet, who has thrown away the shackles of rhythm and numbers, retaining of poetry only its enthusiasm and wild imaginings. Texas and Oregon are his favorite themes.”

A member of the opposing political party, a Whig, took issue with Davezac at Baltimore, derisively calling him a “foreigner” as he had a pronounced Creole French accent. Davezac quickly took up the challenge with rapier-like response:

“I am sorry to interrupt you, but I can permit no man to use such language in my presence. Judging from your appearance, I was an American citizen before you were born. I have a son, born an American citizen, older than you. As for myself, I have been four times naturalized. I was naturalized by the sanctity of the treaty of Louisiana, the highest form of law known to the Constitution. The rights of an American citizen were conferred upon me by the law creating the Territorial Government of Louisiana; and I was admitted to all the rights, blessings, and obligations which belong to you, my fellow citizens, by the law bringing the State of Louisiana into our glorious confederacy,” Davezac said. Then, his eyes flashing as on the plains of New Orleans, he continued, “Sir, you look now as if you desired to know where and when was the fourth time of my naturalization, and who were my sponsors. The consecrated spot on which I received the rights of naturalization was the battle ground of New Orleans; the altar was victory, the baptismal water was blood and fire; Andrew Jackson was my god-father, and patriotism, freedom and glory my god-mothers.” The cheers after this from the crowd were resounding. (Public Ledger, Philadelphia, Oct. 15, 1844)

In a biographical sketch of Davezac published by the Democratic Review in February 1845, the editor wrote “Probably no man has ever listened to the impassioned flow of the gallant old Major’s eloquence without carrying away a lively feeling of personal sympathy and something resembling affectionate attachment for the warm-hearted and enthusiastic speaker.” Davezac had given at least 60 addresses to Democrats in whose case the editor said he was so ardent an advocate, so valiant a champion, he had received 166 invitations in one year to speak publicly in 20 states, which attested to his wide-spread celebrity.

A friend of Gen. Jackson ever since serving as his aide-de-camp during the New Orleans campaign of 1814-1815, Davezac had blossomed in his later years into a major political asset. In 1844, at the age of 63, he made a whirlwind speaking tour by train from his residence in New York City to Philadelphia, Baltimore, Cleveland, Detroit, Trenton, New Jersey, and Winchester, Va.

At the Winchester Democratic rally, he had his biggest audience ever, some 10,000 people from throughout the Old Dominion state. Before he could begin to speak there, the forest rang with three additional cheers for his old friend and Democratic icon Jackson, according to a witness for the Richmond Enquirer who said Davezac “gave the most impassioned, the richest and most effective treat of oratory it was ever our good fortune to enjoy. Its materials were derived from a life of useful effort, study, and observation. He advocated annexation of Texas, a hot topic of the day, and the increasing spread of settlement of the US through Manifest Destiny.

Spotting some men in the group then called “Young Hickories” after Jackson, Davezac eloquently asked them to “support him, now in the evening of life, in a cause which he had labored to promote in its morning and noon, and when they bent over the tomb of Auguste Davezac, he begged they would remember him only as a friend of Liberty and the favored comrade of Andrew Jackson,” stated the witness. Although he was tired from addressing a large meeting the previous night, the breathless audience hanging onto his every word compelled Davezac to speak for two hours straight, during which thousands had not changed the position in which they densely stood, and with such stillness that the rustling of a leaf could be heard amid the spellbound eloquence which swept over them, according to the Richmond reporter.

At the torchlight Democratic procession in Manhattan, Nov. 1, 1844, Davezac carried a banner and a flag, with the banner proclaiming “This Flag Was At the Battle of New Orleans.” Through sheer power of his speeches and his connection to Jackson, Davezac became a national hero to the Democratic party.

Davezac idolized Jackson and deeply cherished his close friendship with him. In March 1842, an elderly and sickly Jackson mostly confined to his bedroom wrote a sad letter to Auguste about how he was trying to put his “house in order to meet that call which must soon come to that other and better world from which no traveller returns.” In reviewing his past, Jackson wrote although he was satisfied with most of his life’s accomplishments, one thing still bothered him, the “iniquity and injustice of the $1,000 fine” imposed by Judge Hall, who believed Jackson had abused martial law during the defense of New Orleans. “Congress is the only body whose action could wipe this stain from my memory, by a joint resolution ordering the fine, with costs and interests, to be returned…going out of life….I cannot but regret that this stain upon my name should be permitted to pass down in posterity.” Davezac had the influence to see to it that a resolution was initiated through his friends in Congress to do as Old Hickory had asked, and Congress did approve the refund in 1844 on the 29th anniversary of the Battle of New Orleans . The old war hero died a year and a half later.

So who was Major Auguste Davezac, the electrifying speaker of the 1840s, and what was his background? Before he met Jackson, he had been a respected lawyer and doctor in New Orleans, the brother-in-law of prominent attorney Edward Livingston, and a close friend of the privateers Jean and Pierre Laffite.

Davezac’s story began in the Caribbean city of Aquin, St. Domingue (now Haiti), where he was born in 1781. His father was wealthy French plantation owner Jean Pierre Valentine D’Avezac de Castera, who saw to it that Auguste went to school in France at the famous military college of La Flèche. Auguste returned to St. Domingue at the time of the slave revolts, and narrowly missed being massacred in 1803 along with two of his brothers and his maternal grandmother when the rest of the family fled in two boats, first to Jamaica, and then to the US. His mother, Marie Talary de Maragon D’Avezac, young widowed sister Louise, and nine year old sister Pauline, moved to New Orleans, where they lived off the sale of some precious jewels they had sewn into their clothes before leaving. Auguste and his father went to Virginia, where Jean Pierre soon died of yellow fever.

Auguste studied medicine with Dr. Dickinson of Edenton, N.C., then had a medical practice at Accomack, on the eastern shore of Virginia. There he met and married an heiress, Margaret Andrews, and they had a son, Augustus D’Avezac, in 1805. Then, for some unknown reason, Auguste left his family at Accomack and moved to New Orleans to be with his sister, Louise, who had married for the second time to prominent lawyer Edward Livingston in 1805. An ad in the July 30, 1807 Orleans Gazette shows that Dr. Davezac “informs the public that he has established his residence at Bourbon St. No. 30.” Auguste had dropped the apostrophe in his surname upon moving, and soon he opted out of his medical practice, too, as he wished to learn law under the tutelage of his brother-in-law Livingston. He lived with the Livingstons for several years, tutored their daughter Cora, and was a junior partner with Edward for a time before branching out into a law practice completely dealing with the criminal court system. According to a contemporaneous biography of him, it was said no client of his ever suffered the death penalty, so adroit and skillful were his defense arguments. New Orleans merchant Vincent Nolte noted in his autobiography that the Laffite brothers often could be seen arm and arm with Davezac, walking about town.

Gen. Andrew Jackson’s arrival in New Orleans in December 1814 led to the highlight of Davezac’s life, when Old Hickory named him aide de camp and judge advocate on his military staff for the defense of the city during the British invasion. He gave him the honorific title Major, which Davezac cherished and used to the end of his life.

“I instinctively foresaw his (Jackson’s) greatness and glory. My attachment to him was a religion of the heart,” Davezac recalled later. Their work together at Chalmette battlefield cemented a bond that time did not dim afterward. As Auguste had been a doctor in his early life, he quite possibly assisted Jackson medically as well during the campaign, since the general was so severely ill at that time there was some doubt he would be able to lead his men.

After the successful defeat of the British at the Battle of New Orleans on Jan. 8, 1815, Davezac kept up his New Orleans legal practice and continued to support Jackson through both the 1824 and 1828 presidential campaigns. As President, Jackson did not forget his friend, but rewarded him in 1831 with a diplomatic post, chargé d’affaires, at the Hague in the Netherlands. Auguste promised to keep the State Department informed of political developments in Europe, which was still in flux from the French 1830 revolution, plus a series of riots and revolutions elsewhere on the Continent, not to mention the secession of Belgium from the Netherlands. The Creole became quite the idol of the diplomatic corps during the eight years he served, and was considered indispensable at all dances and masquerades due to his ready wit and wonderful conversational talents.

Davezac returned to the US in 1839, not to New Orleans, but to set up a home in New York City. There he became the honored living Manhattan connection to the Battle of New Orleans. At the dinner table at events, he often told intimate tales of Jackson and the legendary Jean Laffite. He entered the Democratic political arena with gusto, and was elected in both 1841 and 1843 to the New York State Legislature. He became a fiery supporter of the American expansionist movement of Manifest Destiny, and also was considered one of the most passionate supporters of the Monroe Doctrine. The man of many talents also took up his pen and wrote articles for his favorite publication, the Democratic Review magazine, in the early 1840s.

Recalling a scene from the flower markets at Amsterdam, Davezac wrote, “At Amsterdam, classes from all societies assemble at the flower markets held twice a week. The rich attend to purchase ‘the emerald, the rubies, the sapphires of the vegetable kingdom; flowers are taken to the home of the poor to light the gloom of a homely shed__to give sweetness to the little air yet allowed to breathe. All clustered around them (the flowers) like bees, and like bees, appeared to gather from them nothing but sweetness.”

His literary, speaking, and political talents brought him into the orbit of such celebrated poets and writers as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, and the Melville brothers.

After helping Polk win the Presidency in the 1844 election, Davezac was re-appointed as chargé d’affaires at the Hague in 1845. He returned home to the US on Jan. 8, 1851, and died about a month later, at the age of 69.

Today the charismatic Creole veteran of the Battle of New Orleans is little remembered as the sands of time have dimmed his accomplishments and celebrity. He was a visionary concerning Manifest Destiny, believing it was the destiny of the United States to expand its territory over the whole of North America and to extend and enhance its political, social, and economic influences. Federalists of the time scoffed and held the opinion the US already had land enough, which formed the focus of Davezac’s speeches on the subject, as the following illustrates, in closing:

“Land enough! Make way, I say, for the young American Buffalo__he has not yet got land enough. He wants more land as his cool shade in summer; he wants more land for his beautiful pasture grounds. I tell you we will give him Oregon for his summer shade and the region of Texas as his winter pasture. Like all of his race, he wants salt, too. Well, he shall have the use of two oceans, the mighty Pacific and turbulent Atlantic shall be his; for I tell you that the day is not far distant when with one leap he shall bound across the puny lakes that separate Canada from America ad pitch right into the other side…He shall not stop his career until he slakes his thirst in the frozen ocean,” predicted Davezac at the 1844 Trenton, N.J. Great Mass meeting of Democrats.

Well, Major Davezac, the US did not expand into Canada, but did get to the frozen ocean around Alaska, the volcanic islands of Hawaii, and from the coast of the Atlantic to the coast of the Pacific on the land mass…

Related Articles

Andrew Jackson’s Fine and the Place of Martial Law in American Politics

Recent Comments